Rarely have science and government been as clearly linked as the initial response to the Covid-19 pandemic, when politicians could be heard claiming they were being ‘led by the science’ as often as they could be seen doing that pointing-with-a-thumb-and-fist thing.

This Thursday, the UK’s Chief Scientific Adviser, Sir Patrick Vallance, will receive the Lister Medal for his leadership during the Covid-19 pandemic, and you can stream it live here, exclusively on SCI’s YouTube channel!

In readiness for Sir Patrick’s lecture, Eoin Redahan looks back at three ways science helped to mitigate the spread of Covid-19.

People will never look at vaccine development the same way. For good or ill, we have realised just how quickly they can now be developed. Similarly, we have realised what can be achieved when the brightest brains come together. These are two of the positive legacies from Covid.

But there are others. Some of the innovations conceived to tackle Covid will now tackle other pathogens. Here are just three of the innovations that emerged…

1. Wastewater warning

As Oscar Wilde once said: ‘We are all in the gutter, but some of us are looking up at the genetic material in stool samples.’

Not many people would find inspiration in wastewater treatment plants when thinking about early warning systems for infectious diseases.

Nevertheless, during the Covid-19 pandemic, researchers at TU Darmstadt in Germany came up with a system that detected Covid infection rates in the general population by analysing their waste – a system so accurate they could detect the presence of Covid among those without recognisable symptoms.

To do this, they examined the genetic material in samples from Frankfurt’s wastewater plants and tested them using the PCR test. They claim that their measurement was so sensitive it could detect fewer than 10 confirmed Covid-19 cases per 100,000 people.

It is inevitable that Covid-19 variants will rise again, but this system could alert us to the need for tighter protective measures as soon as the virus appears in our wastewater.

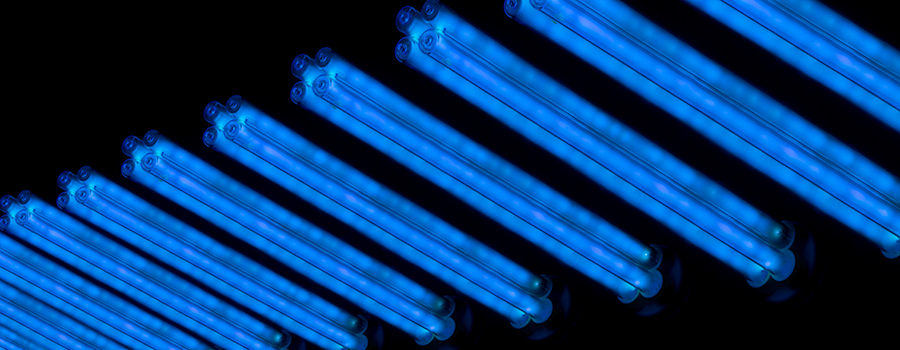

2. UV air treatment

UV light can reportedly reduce indoor airborne microbes by 98%.

Warning systems are important, as are ways to stop the spread of pathogens. To do this, a team from the UK and US shed light on the problem – well, they used ultraviolet light to remove the pathogens.

Using funding from the UK Health Security Agency, Columbia University researchers discovered that far-UVC light from lights installed in the ceiling almost eliminate the indoor transmission of airborne diseases such as Covid-19 and influenza.

The researchers claim it took less than five minutes for their germicidal UV light to reduce indoor airborne microbe levels by more than 98% – and it does the job as long as the light remains switched on.

‘Far-UVC rapidly reduces the amount of active microbes in the indoor air to almost zero, making indoor air essentially as safe as outdoor air,’ said study co-author David Brenner, director of the Center for Radiological Research at Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons. ‘Using this technology in locations where people gather together indoors could prevent the next potential pandemic.’

3. Biological masks?

‘Physical mask, meet biological mask.’

Many moons ago, it was strange to see a person wearing a mask, even in cities with dubious air quality. Now, they are ubiquitous, and it would appear that mask innovations are everywhere too.

During Covid, researchers from the University of Granada in Spain were aware that wearing masks for a long time could be bad for our health. They devised a near field communication tag for inside our FFP2 masks to monitor CO2 rebreathing. This batteryless, opto-chemical sensor communicates with the wearer’s phone, telling them when CO2 levels are too high.

In the same spirit, researchers in Helsinki, Finland, developed a ‘biological mask’ to counteract Covid-19. The University of Helsinki researchers developed a nasal spray with molecule (TRiSb92) that deactivates the coronavirus spike protein and provides short-term protection against the virus – a sort of biological mask, albeit without those annoying elastics digging into our ears.

‘In animal models, nasally administered TriSb92 offered protection against infection in an exposure situation where all unprotected mice were infected,’ said Anna Mäkelä, postdoctoral researcher and study co-author.

‘Targeting this inhibitory effect of the TriSb92 molecule to a site of the coronavirus spike protein common to all variants of the virus makes it possible to effectively inhibit the ability of all known variants.’

The idea is for this nasal spray to complement vaccines, though during peak Covid paranoia, it might be tricky persuading everyone on the bus that you’re wearing a biological mask.

Covid disrupted scientific progress for many, but as we know, invention shines through in troublesome times. Plenty of innovations such as the ones above will make us better equipped to tackle air borne diseases – alongside the stewardship of leaders like Sir Patrick Vallance.

Watch Sir Patrick Vallance’s talk – Government, Science and Industry: from Covid to Climate – at 18:25 on 24 November

Those with the blood group O reportedly have the lowest likelihood of catching Covid-19, and the new top-up jab should provide relief against sub-variants of the disease.

By now, most of us have been stricken by Covid, but 15% of people in the UK have evaded the virus. According to a testing expert at the London Medical Laboratory, the great escape is down to three factors: blood group, vaccines, and lifestyle.

Having assessed the findings of recent Covid-19 blood type studies, Dr Quinton Fivelman PhD, Chief Scientific Officer at London Medical Laboratory (LML), believes that people with the blood group O are less likely to be infected than those with other blood groups, while those with blood type A are far more likely to contract the virus.

‘There have now been too many studies to ignore which reveal that people have a lower chance of catching the virus, or developing a severe illness, if they have blood group O,’ he said.

Indeed, research from the New England Journal of Medicine had previously found that those with blood type O were 35% less likely to be infected, whereas those with Type A were 45% more vulnerable. A further benefit of type O blood is the reduced risk of heart disease compared to those with type A or B blood.

>> What is the ideal body position to adopt when taking a pill? Wonder no more.

Staged stock images are not thought to increase your chances of contracting Covid-19.

According to the NHS, almost half of the population (48%) has the O blood group; so, clearly, other factors come into play in terms of our susceptibility. Dr Fivelman said: ‘By far the most important factor is the number of antibodies you carry, from inoculations and previous infections, together with your level of overall health and fitness.’

Tackling the sub-variants

So, those who are more careful about visiting crowded places, who eat well, and are fortunate enough not to have an underlying illness have better chances of avoiding Covid-19. According to LML, having been vaccinated also helps, though these benefits have slowly worn off. That is why the new top-up jab with the Omicron variant could provide some relief for those who take it.

‘The new Omicron jab has come none-too-soon, so many people are now suffering repeated Covid infections,’ he added. ‘That’s because the new Omicron BA.4 and BA.5 sub-variants do not produce as high an immune response as the previous strains, so re-infection is more likely to occur.

‘Higher levels of antibodies are important to neutralise the virus, stopping infection and limiting people transmitting the virus to others.’

>> Which herbs could boost your wellbeing? Dr Vivien Rolfe tells us more.

From the Black Death to the Covid-19 pandemic, great adversity has also led to great advances. So, which inventions have emerged from times of hardship? Eoin Redahan finds out.

‘World events shape innovations. The World Wars shaped innovation, and the pandemic has shaped innovation,’ said Paul Booth OBE, in his outgoing speech as SCI President.

‘It is possible to accelerate innovation – we’ve demonstrated that.’ Paul Booth OBE, outgoing SCI President at SCI’s AGM, July 2022. Image: SCI/Andrew Lunn

The pandemic taught us a lot about ourselves. It taught me that eating my body weight in sweets was a great way to destroy my teeth, and it brought home to many the futility of the five-day commute. On a more abstract level, it taught governments and policy makers just how much can be achieved in a short space of time when necessity demands it. The vaccines that swam around our veins bore testament to this.

The pandemic has shaped innovation. Nowhere is this more apparent than in medicine. It isn’t the first awful event to provide a hotbed for change, and it won’t be the last. ‘It is possible to accelerate innovation,’ Paul said. ‘We’ve demonstrated that.’

Black Death and the bird mask

As bad as the Covid-19 pandemic was, the Black Death makes it look very tame indeed. It is estimated that the Plague, which was its worst from 1346-53, took up to 200 million lives in Eurasia and North Africa.

Amid the carnage, it is also said to have given us a system to mitigate infectious diseases with which we are familiar, including isolation periods. According to Britannica, ‘public officials created a system of sanitary control to combat contagious diseases, using observation stations, isolation hospitals, and disinfection procedures.’

The terrifying doctor will see you now.

The Plague also said to have inspired greater experimentation in pharmacology. In a sense, it also helped democratise medicine, with medical textbooks shifting from Latin to the vernacular. As John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, noted: ‘Both medical and religious practice now shifted toward the laity.’

But perhaps the most memorable advance from this time was the strange, beak-like masks worn by some doctors during the Plague. These masks were a crude (and frankly terrifying) way to protect the doctors from the disease in the air. The doctors even filled these masks with herbs in an effort to protect against pathogens.

Byproducts of the war effort

Of course, wars have also led to military innovation at breakneck speed. During the American Civil War, the Minié ball was created. It spun faster than other bullets and could travel half a mile – unlike pre-Civil War bullets, which went a mere 300 feet.

Officers of a monitor-class ironclad warship, photographed during the American Civil War.

This war also led to the ironclad warship, with plates riveted together to protect against cannonballs. However, it should also be noted that many of the most interesting war-borne inventions have ended up having little or nothing to do with military application.

The ‘cotton-like-texture’ of cellucotton led to its brand name Kotex. According to this 1920 advertisement, this ‘wardrobe essential of Her Royal Daintiness’ was available at any shop that catered to women. Different times.

World War I gave us the blood bank, the Kleenex, the trench coat, and the sanitary pad. The sanitary pad has peculiar origins. In 1914, the war resulted in cotton shortages and substitutes were needed. Kimberly-Clark executives duly discovered a processed wood pulp material that was five times more absorbent than cotton, and cheaper to make. The material was used for bandages, and Red Cross nurses realised that this material could be used as makeshift sanitary pads. The company then developed a sanitary pad – branded Kotex – made from cellucotton and a fine gauze.

Synthetic rubber and Super Glue

Material substitution also led to ground-breaking innovation in World War II. According to the National WWII Museum New Orleans, in 1942 Japan cut off the US supply of natural rubber. With the demand for rubber high, US President Franklin Roosevelt invested $700m to make synthetic rubber from petrochemical byproducts at 51 new plants. By 1944, these synthetic rubber plants were producing 800,000 tonnes of the material a year.

Duct tape was developed by Johnson & Johnson during the Second World War, and by 1972 the ubiquitous tape had reached the moon. This makeshift wheel fender repair helped the Apollo 17 mission’s lunar rover to keep lunar dust at bay.

We use many other products invented during the Second World War, including duct tape, which was developed by Johnson & Johnson to keep moisture out of ammunition cases. A fellow called Harry Coover discovered cyanoacrylates – the active ingredient in Super Glue – while he tried to create a clear plastic for gun sights.

And the next time you reheat your dinner, spare a thought for Percy Spencer, the US physicist who noticed the candy bar melting in his pocket when he stood next to an active radar set. This moment of epiphany led to an invention you might know: the humble microwave.

Accelerating penicillin and vaccine rollout

Just as these trying times lead to extraordinary leaps in technology, they also lead to the large-scale rollout of said discoveries. A prime example of this is penicillin. It was first used to treat an eye infection in 1930, but it was only with the horrific fall-out of war that experiments with deep tank fermentation led to its widespread production.

A soldier recuperates in hospital thanks to penicillin in this Second World War poster. Note the not-quite-so-life-saving hospital bed cigarette. Different times, again.

The Penicillin Production through Deep-tank Fermentation paper in ACS notes that: ‘During World War II, the governments of the United States and the UK approached the largest US chemical and pharmaceutical companies to enlist them in the race to mass produce penicillin […] One of these companies, Pfizer, succeeded in producing large quantities of penicillin using deep-tank fermentation.’

The speed of development and global-scale rollout of vaccines against Covid-19 was unprecedented. Science, business and governments worked together to get the world moving again.

And, as we all know, Pfizer was back at it again during the Covid-19 pandemic. Along with AstraZeneca, Moderna, and essentially the entire pharmaceutical industry, it created vaccines that saved countless lives. Governments and policymakers were also reminded just how quickly life-saving technologies can be pushed through when needed.

But the legacy of Covid-19 treatment will stretch further, be it in nanotechnology, artificial intelligence, or other fields – who knows what else will come from it?

As Paul Booth said: ‘It is possible to accelerate innovation. We’ve demonstrated that.’

A year after the world was put on alert about the rapidly spreading covid-19 virus, mass vaccination programmes are providing a welcome light at the end of the tunnel.

However, for many people vaccination remains a concern. A World Economic Forum – Ipsos survey: Global Attitudes on a Covid-19 Vaccine, indicates that while an increasing number of people in the US and UK plan to get vaccinated, the intent has dropped in South Africa, France, Japan and South Korea. The survey was conducted in December 2020, following the first vaccinations in the US and the UK.

This study shows that overall vaccination intent is below 50% in France and Russia. ‘Strong intent’ is below 15% in Japan, France and Russia.

Many cities are still in lockdown

Between 57% and 80% of those surveyed cited concerns over side effects as a reason for not getting a covid-19 vaccination. Doubts over the effectiveness of a vaccine was the second most common reason cited in many countries, while opposition to vaccines in general was mentioned by around 25% those who will refuse a vaccination.

The survey was conducted among 13,542 adults aged 18–74 in Canada, South Africa, and the US, while those surveyed in Australia, Brazil, China, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, Mexico, Russia, South Korea, Spain and the UK were aged 16–74.

A previous survey, Global Attitudes on a Covid-19 Vaccine carried out in July and August 2020, indicated that 74% of those surveyed intended to get vaccinated. At that time the World Economic Forum said that this majority could still fall short of the number required to ‘beat covid-19.’

Commenting on the newest data Arnaud Bernaert, Head of Health and Healthcare at the World Economic Forum said; ‘As vaccinations roll out, it is encouraging to see confidence improve most in countries where vaccines are already made available. It is critical that governments and the private sector come together to build confidence and ensure that manufacturing capacity meets the global demand.’

World Economic Forum-Ipsos Survey indicates a rise in number of people in US and UK intending to get vaccinated.

With the imperative now to move towards some sort of ‘normality’, as well as getting economies moving, fears over vaccination need to be allayed. However, what also needs to be considered is what underlies those fears. Misinformation, no doubt, has a part to play. This highlights a lack of trust in governments and a sector that has worked tirelessly to develop vaccines in record time.

As different companies bring their vaccines to the market, care now needs to be taken to reassure people around the world that whichever manufacturer’s vaccine they are given, they are in safe hands. As any adverse reactions occur – an inevitability with any vaccine rollout – these ought to be made known to the wider public by companies and governments as soon as it is feasible, preventing space for the spread of rumour and misinformation, which could undo the hard work of the scientists, businesses and governments bringing vaccines to the public.

Researchers have worked tirelessly to bring vaccines to the market