What effect do vaping and air pollution have on your heart, and how could a light-powered pacemaker improve cardiovascular health?

It seems that every day, scientists are learning more about the factors affecting cardiovascular health and are coming up with novel ways to keep our hearts ticking for longer. Here are three interesting recent developments.

A less painful pacemaker

One of the problems with existing pacemakers is that they are implanted into the heart with one or two points of connection (using screws or hooks). According to University of Arizona researchers, when these devices detect a dangerous irregularity they send an electrical shock through the whole heart to regulate its beat.

These researchers believe their battery-free, light-powered pacemaker could improve the quality of life of heart disease patients through the increased precision of their device.

The way existing pacemakers work can be quite painful for heart disease patients.

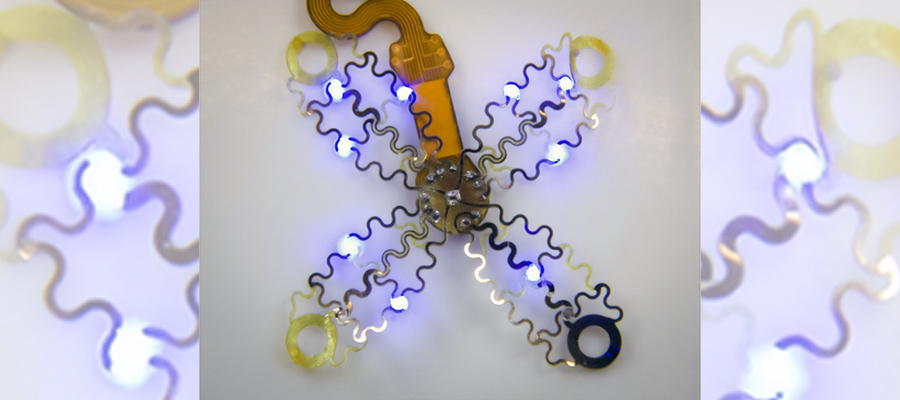

Their pacemaker comprises a petal-like structure made from a thin flexible film (that contains light sources) and a recording electrode. Like the petals of a flower closing up at night, this mesh pacemaker envelops the heart to provide many points of contact.

The device also uses optogenetics – a biological technique to control the activity of cells using light. The researchers say this helps to control the heart far more precisely and bypass pain receptors.

‘Right now, we have to shock the whole heart to do this, [but] these new devices can do much more precise targeting, making defibrillation both more effective and less painful,’ said Igor Efimov, professor of biomedical engineering and medicine at Northwestern University.

‘Current pacemakers record basically a simple threshold, and they will tell you,’ added Philipp Gutruf, lead researcher and biomedical engineering assistant professor. ‘This is going into arrhythmia, now shock, but this device has a computer on board where you can input different algorithms that allow you to pace in a more sophisticated way.’

Another potential benefit is that the light-powered device could negate the need for battery replacement, which is done every five to seven years. That use of light to affect the heart rather than electrical signals could also mean less interference with the device’s recording capabilities and a more complete picture of cardiac episodes.

The device uses light and a technique called optogenetics, which modifies cells that are sensitive to light, then uses light to affect the behavior of those cells. Image by Philipp Gutruff.

>> See how Bright SCIdea winner Cardiatec uses AI to improve heart disease treatment.

The danger of vaping?

We don’t know a lot about the long-term effects of vaping because people simply haven’t been doing it long enough, but a recent study from the University of Wisconsin (UW) suggests that it could be bad for the heart.

Researchers selected a group of people who had used nicotine delivery devices for 4.1 years on average, those who smoked cigarettes for 23 years on average, and non-smokers and compared how their hearts behaved after smoking (the first two groups) and after exercise.

The researchers noticed differences minutes after the first two groups smoked or vaped. ‘Immediately after vaping or smoking, there were worrisome changes in blood pressure, heart rate, heart rate variability and blood vessel tone (constriction),’ said lead study author Matthew Tattersall, an assistant professor of medicine at the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health.

The lack of long-term data means we still don’t know the effect of vaping.

Those who vaped also performed worse on the four exercise parameters compared to those who hadn’t used nicotine. Perhaps the most startling finding was the post-exercise response of those who had vaped for just four years compared to those who had smoked tobacco for 23 years.

‘The exercise performance of those who vaped was not significantly different from people who used combustible cigarettes, even though they had vaped for fewer years than the people who smoked and were much younger,’ said Christina Hughey, fellow in cardiovascular medicine at UW Health, the integrated health systems of the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

The influence of lead and air pollution

We know that smoking and passive-smoking are bad for our hearts, but some overlook the effect of other environmental toxins, especially those common to specific geographical regions.

A collaborative study including US and UK researchers has found a divergence in the types of environmental contaminants that contribute to cardiovascular ailments in both countries, aside from the prevalent smoking-related heart disease.

Hopefully, the growth in electric vehicle use will reduce air pollution

The study found that lead-related poisoning is more common in the US, whereas air pollution has a more damaging effect in the UK due mainly to increased population density. The researchers found that 6.5% of cardiovascular deaths were associated with exposure to particulate matter over the past 30 years compared to 5% in the US.

The one plus is that research has found that there has been a steady decline in cardiovascular deaths stemming from lead, smoking, secondhand smoke and air pollution over the past 30 years. Nevertheless, it will be of little comfort to those walking in the trail of exhaust fumes in cities.

‘More research on how environmental risk factors impact our daily lives is needed to help policymakers, public health experts, and communities see the big picture,’ said lead author Anoop Titus, a third-year internal medicine resident at St. Vincent Hospital in Worcester, Massachusetts.

Rarely have science and government been as clearly linked as the initial response to the Covid-19 pandemic, when politicians could be heard claiming they were being ‘led by the science’ as often as they could be seen doing that pointing-with-a-thumb-and-fist thing.

This Thursday, the UK’s Chief Scientific Adviser, Sir Patrick Vallance, will receive the Lister Medal for his leadership during the Covid-19 pandemic, and you can stream it live here, exclusively on SCI’s YouTube channel!

In readiness for Sir Patrick’s lecture, Eoin Redahan looks back at three ways science helped to mitigate the spread of Covid-19.

People will never look at vaccine development the same way. For good or ill, we have realised just how quickly they can now be developed. Similarly, we have realised what can be achieved when the brightest brains come together. These are two of the positive legacies from Covid.

But there are others. Some of the innovations conceived to tackle Covid will now tackle other pathogens. Here are just three of the innovations that emerged…

1. Wastewater warning

As Oscar Wilde once said: ‘We are all in the gutter, but some of us are looking up at the genetic material in stool samples.’

Not many people would find inspiration in wastewater treatment plants when thinking about early warning systems for infectious diseases.

Nevertheless, during the Covid-19 pandemic, researchers at TU Darmstadt in Germany came up with a system that detected Covid infection rates in the general population by analysing their waste – a system so accurate they could detect the presence of Covid among those without recognisable symptoms.

To do this, they examined the genetic material in samples from Frankfurt’s wastewater plants and tested them using the PCR test. They claim that their measurement was so sensitive it could detect fewer than 10 confirmed Covid-19 cases per 100,000 people.

It is inevitable that Covid-19 variants will rise again, but this system could alert us to the need for tighter protective measures as soon as the virus appears in our wastewater.

2. UV air treatment

UV light can reportedly reduce indoor airborne microbes by 98%.

Warning systems are important, as are ways to stop the spread of pathogens. To do this, a team from the UK and US shed light on the problem – well, they used ultraviolet light to remove the pathogens.

Using funding from the UK Health Security Agency, Columbia University researchers discovered that far-UVC light from lights installed in the ceiling almost eliminate the indoor transmission of airborne diseases such as Covid-19 and influenza.

The researchers claim it took less than five minutes for their germicidal UV light to reduce indoor airborne microbe levels by more than 98% – and it does the job as long as the light remains switched on.

‘Far-UVC rapidly reduces the amount of active microbes in the indoor air to almost zero, making indoor air essentially as safe as outdoor air,’ said study co-author David Brenner, director of the Center for Radiological Research at Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons. ‘Using this technology in locations where people gather together indoors could prevent the next potential pandemic.’

3. Biological masks?

‘Physical mask, meet biological mask.’

Many moons ago, it was strange to see a person wearing a mask, even in cities with dubious air quality. Now, they are ubiquitous, and it would appear that mask innovations are everywhere too.

During Covid, researchers from the University of Granada in Spain were aware that wearing masks for a long time could be bad for our health. They devised a near field communication tag for inside our FFP2 masks to monitor CO2 rebreathing. This batteryless, opto-chemical sensor communicates with the wearer’s phone, telling them when CO2 levels are too high.

In the same spirit, researchers in Helsinki, Finland, developed a ‘biological mask’ to counteract Covid-19. The University of Helsinki researchers developed a nasal spray with molecule (TRiSb92) that deactivates the coronavirus spike protein and provides short-term protection against the virus – a sort of biological mask, albeit without those annoying elastics digging into our ears.

‘In animal models, nasally administered TriSb92 offered protection against infection in an exposure situation where all unprotected mice were infected,’ said Anna Mäkelä, postdoctoral researcher and study co-author.

‘Targeting this inhibitory effect of the TriSb92 molecule to a site of the coronavirus spike protein common to all variants of the virus makes it possible to effectively inhibit the ability of all known variants.’

The idea is for this nasal spray to complement vaccines, though during peak Covid paranoia, it might be tricky persuading everyone on the bus that you’re wearing a biological mask.

Covid disrupted scientific progress for many, but as we know, invention shines through in troublesome times. Plenty of innovations such as the ones above will make us better equipped to tackle air borne diseases – alongside the stewardship of leaders like Sir Patrick Vallance.

Watch Sir Patrick Vallance’s talk – Government, Science and Industry: from Covid to Climate – at 18:25 on 24 November

What does clean smell like? What if the fragrance you want to create is that of a sweet-smelling, yet poisonous, flower? In his Scientific Artistry of Fragrances SCITalk, Dr Ellwood led us by the nose.

When Dr Simon Ellwood spoke about creating a fragrance, it sounded like a musical composition or a painting. The flavourist, sitting before a palette of 1,500 fragrance ingredients. Each occupies a different note on the register: the top notes, the middle ones, and the bottom.

To the outsider, this seems impossibly vast and daunting. The Head of Health & Wellbeing Centre of Excellence – Fragrance and Active Beauty Division at Givaudan mentioned that Persil resolved to come up with ‘the smell of clean’ for its detergents in the late 1950s.

But what should clean smell like? Should it be the green, citrusy aromas of this laundry detergent, the smell of mint, or the antiseptic at the hospital?

To make choosing smells slightly less daunting for flavourists and perfumers, they are at least split into odour families such as citrus, floral, green, fruity, spicy, musky, and woody. Some of these ingredients are natural, some are inspired by nature, and others come from petrochemicals and synthetic materials.

The delicious-smelling musk deer.

Deer gland perfume

One of the smells you may have sprayed on your person – one sibling in this odour family – has peculiar origins. The pleasant, powdery smell known as musk was originally extracted from the caudal gland of the male musk deer and from the civet cat.

But as the Colognoisseur website notes, as many as 50 musk deer would have to be killed to obtain one kilogramme of these nodules. Now, killing a load of deer and cats for a few bottles of perfume may not have seemed unethical several centuries ago, but it also wasn’t sustainable or cost-effective. It became clear that a synthetic musk was needed.

When the synthetic musk discovery came in 1888, it was a chance discovery. Albert Bauer had been looking to make explosives when a distinctive smell came instead, along with the scent of opportunity.

>> Read about the science behind your cosmetics

Dior recreated the woodland notes of Lily of the valley.

Do you like the smell of jasmine?

Dr Ellwood’s talk laid bare not only the vastness of everything we smell, but also the ingenuity of those who recreate these odours. In terms of breadth of smell, neroli oil – which is taken from the blossom of a bitter orange – has floral, citrus, fresh, and sweet odours, with notes of mint and caraway. Similarly, and yet dissimilarly, jasmine’s odour families are broken down into sweet, floral, fresh, and fruity, and – jarringly – intensely fecal.

The ingenuity of flavourists is exemplified by lily of the valley. The woodland, bell-shaped flowers are known for their evocative smell, but all parts of the plant are poisonous. Despite this, French company Dior synthetically recreated the lily of the valley smell in its Diorissimo perfume in 1956 using hydroxycitronellal, which is described by the Good Scents Company as having ‘a sweet floral odour with citrus and melon undertones’.

Cyanide smells like almonds, but you might not want to eat it.

Of course, as Dr Ellwood noted, synthetic flavours can only ever get so close to the real thing – an imperfect facsimile. However, the mere fact that chemists have recreated deer musk, lily of the valley, and the prized ambergris from sperm whales to create the fragrances we love is almost as extraordinary as the smells themselves.

‘Fragrance,’ he said, ‘will always be the confluence of the artistry of the perfumer and the chemist.

Register for our free upcoming SCI Talk on the Chemistry behind Beauty & Personal Care Products.

Little machines that blend makeup tailored for your skin alone… Technology that details the tiny creatures walking on your face… The cosmetic revolution is coming, and Dr Barbara Brockway told us all about it.

Max Huber burnt his face. The lab experiment left him scarred, and he couldn’t find a way to heal it. So, he turned to the sea. Inspired by the regenerative powers of seaweed, he conducted experiment after experiment – 6,000 in all – until he created his miracle broth in 1965. You might know this moisturiser as Crème de la Mer.

A rocket scientist in the world of cosmetics seems strange, but when you interrogate it, it isn’t strange at all. As Dr Barbara Brockway, a scientific advisor in cosmetics and personal care, explained in our latest SCItalk, cosmetics hang from the many branches of science.

Engineering, computer science, maths, biology, chemistry, statistics, artificial intelligence, and bioinformatics are among the disciplines that create the creams you knead into your face, the sprays that stun your hair in place. They say it takes a village to raise a child, and it takes an army of scientists to formulate all the creams, gels, lotions, body milks, and sprays in your cupboard.

Some say sea kelp can be used to treat everything from diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, and cancer, to repairing your nails and skin.

There is a reason why the chemistry behind these products is so advanced. If you sell bread, it is made to last a week. If you make a moisturising cream, it is formulated to last three years. To make sure it does that, chemists test it at elevated temperatures to speed up the time frame. They conduct vibration tests and freeze-thaw tests to measure its stability.

Dr Brockway likened the process of bringing a product to market to a game of snakes and ladders. If you climb enough ladders, you could take your own miracle brew to market within 10 months.

But expectations are high, and the product must delight the user. Think of the teenager who empties a half a can of Lynx Africa into his armpit, or the perfume that is a dream inhaled. Each smell she likened to a musical composition.

But these formulators are not struggling artists. Perfumers and cosmetic chemists – these bottlers of love and longing and loss – can earn a fortune. Dr Brockway’s quick calculation provided a glimpse of the lucre.

Take 15kg of the bulk cream you mixed on your kitchen table. That same cream could be turned into 1,000 15ml bottles, each sold for £78. So, just 15kg of product could fetch £78,000. So, it’s easy to see why the global beauty market is worth $483 billion (£427 billion), with the UK market alone worth £7.8 billion – more than the furniture industry.

Smart mirror, mirror, on the wall…

It’s unsurprising that an industry of such value and scientific breadth embraces the latest technologies, from those found in our phones to advances in genetics and the omics revolution.

Already, the digital world has left the makeup tester behind. Smart mirrors overlay virtual makeup, recommend products for your complexion, and even detect skin conditions. Small machines that look like coffee-makes blend bespoke makeup. Indeed, Dr Brockway noted that Yves Saint Laurent has created a blender that produces up to 15,000 different shades.

Even blockchain has elbowed into the act. It is being used to make sure that a product’s ingredients aren’t changed in between batches. By showing customers every time-stamped link of the supply chain, companies can prove that their products are organic or ethically sourced. The reason why blockchain is significant here is that, once recorded, the data stored cannot be amended.

At first glance, proving the provenance of materials to customers might seem like a marketing ploy, but this is also being done in response to the increasing fussiness of the consumer.

Collagen is the main component of connective tissue.

Dr Brockway said all brands are now under pressure to incorporate sustainability into their business practices. The younger age group is also looking for more organic, vegan-friendly ingredients, and businesses have had to respond.

For example, microbial fermentation is being used instead of roosters’ coxcombs to create hyaluronic acid. Similarly, Geltor claims to have created the first ever biodesigned vegan human collagen for skincare (HumaColl21®). Such collagen is usually provided by our friends the fish.

These advances are significant, certainly to the life expectancies of roosters and fish, but of such ingredients revolutions are not made. Other forces will shake the industry.

Meditating on omics

Back in the 1970s, scientists thought the microbes that live on our skin were simple, but next-generation DNA technology reveals that thousands of species of bacteria live on our skin (a pleasant thought). Dr Brockway says these microbes tell us about our lifestyles – to the point that they even know if you own a pet.

So, what is the significance of this? Developments in DNA technology and omics (various disciplines in biology including genomics, proteomics, metagenomics, and metabolomics) mean we can now get not just a snapshot, but an entire picture of what’s going on on your face.

‘Thanks to omics we really know what’s now going on with our skin and see what our products are doing,’ Dr Brockway said. ‘We know the target better. We know which collagens, out of the 263, we need to encourage.’

We are learning more and more about how our skin behaves. And those time-honoured potions and lotions espoused by our grandparents – it will make sense soon, not just why they work, but why they work for some and not for others. In cosmetics, we are leaving the era of checkers and entering the age of chess.

This is the first of three cosmetic SCItalks between now and Christmas. Register now for the Scientific artistry of fragrances.

Reading outside his research area and efficient chemistry helped 2022 Perkin Medal winner Dennis Liotta develop groundbreaking drugs.

There has been an explosion of statistics in football, but one of the most influential figures in this revolution, Ramm Mylvaganam, didn’t care for the game. He worked for the confectionary company Mars. He sold chairs. He knew nothing about football.

However, this key figure outlined in Rory Smith’s recent book, Expected Goals: The story of how data conquered football, came into the field of football analysis and changed the game forever – partly because he approached the game with the fresh perspective of the outsider.

So, what do football statistics have to do with a chemist who came up with life-saving medications? Well, Dr Dennis Liotta, who came up with AIDS antivirals that have saved thousands of lives, may not have entered medicinal chemistry as a complete outsider. He was a chemist, after all. However, like Ramm Mylvaganam, his broad breadth of knowledge from different areas gave him a unique perspective on a new field.

Reading at random

Dr Liotta didn’t take the standard path into medicinal chemistry. In fact, he wasn't a diligent chemistry student at first – and that, in an odd way, contributed to his later success.

For the first couple of years at university, he was more interested in his extracurricular activities; but in his third year, he realised he needed to catch up. He worked hard and burnt the midnight oil. He also did something unusual.

‘I did something that’s kind of ridiculous-sounding,’ he said. ‘I had this big fat organic chemistry book, and I would just open it up randomly to some page and read 10 or 12 pages and close it back up. Over time, I ended up covering not only the things I missed, but actually learning about a lot of things that wouldn't have been covered.’

As his career progressed, Dr Liotta realised the importance of not just working harder, but working smarter. On Sundays, he would sit down with a bunch of academic journals to stay abreast of developments. However, as he read them, he discovered other papers – ones outside his research area – that piqued his interest.

Dennis Liotta in one of his lab spaces at Emory. Image by Marcusrpolo.

‘I’d see something intriguing. And so I’d say, that’s interesting, let me read. I started learning about things that I didn’t technically need to know about, because they were outside of my immediate interest. But those things really changed my life. And, ultimately, I think they were the differentiating factor.’

The intellectual stretch

This intellectual curiosity led to more than 100 patents, including a groundbreaking drug in the fight against AIDS that is still used today and a hand in developing an important hepatitis C drug.

‘In science, many times the people who actually make the most significant innovations are the people who come at a problem that’s outside of their field,’ Dr Liotta said. ‘Without realising it, we all get programmed in terms of how we think about problems, what we accept as fact.’

‘But when you come at a problem that’s outside your field… you aren't immersed in it. So, you think about the problems differently. And many times, in thinking about the problems differently, you’ll come up with an alternative solution that people in the field wouldn’t.’

We’ve often heard the stories of Steve Jobs wandering into random classes while at university when he should have been attending his actual course. Apparently, a calligraphy class inspired the font later used in Apple’s products. In other words, early specialism can sometimes hinder creativity.

‘I've looked into people who have made really some amazing contributions, and many times there’s been an intellectual stretch,’ Dr Liotta said. ‘They’ve gone out there and done something that they weren’t really trained to do. You can fall on your face from time to time, but it’s really nice when we're able to make contributions in areas where we don’t really have any formal training.’

Chance favours…

Of course, there’s so much more to creating life-saving drugs than intellectual curiosity and a different way of thinking. Dr Liotta and his colleagues had the technical skill to turn their ideas into something real. He was a skilled chemist who teamed up with an excellent virologist, Raymond Schinazi. The result of this blend of their skills gave them an edge over others developing AIDS therapeutics.

Dr Liotta invented breakthrough HIV drug Emtricitabine.

‘The very first thing we did was we figured out a spectacular way of preparing the compounds – very clean, very efficient,’ he said. ‘And that [meant we could] explore all sorts of different permutations around the series of compounds that others couldn’t easily do, because their methods were so bad for making [them].

‘So, even though we were competing against some very important pharmaceutical companies that had infinitely more money than we had – dozens of really smart people they put on the project – we were able to run circles around them because we had a really efficient methodology and that enabled us to make some compounds.’

The amazing thing is that the very first compound and the third compound the pair came up with led to FDA-approved drugs. It is a fine thing, indeed, when skill and serendipity meet.

‘Chance favours the prepared mind,’ Dr Liotta said, ‘or, as my colleagues say: you work hard to put yourself in a position to get lucky.’

>> Learn more about Dr Liotta’s career path and research from our recent Q&A.

From luminescent polymer nanoparticles that improve rural healthcare to compostable plastic packaging, Dr Zachary Hudson and his research group at the University of British Columbia are developing solutions to pressing issues.

For those of us who live in cities, we take easy access to hospitals for granted, but what about those in remote areas? What if there were an easier way to diagnose diseases and improve healthcare for those in secluded rural areas?

Luminescent dyes used to make fluorescent Pdots.

Well, Dr Zachary Hudson and his group at the University of British Columbia (UBC) in Canada are developing luminescent polymer nanoparticles that could provide portable, low-cost tools for bio-imaging and analysis in rural areas. These nanoparticles are so bright that they can be detected by smartphone, helping clinicians quantify chemical substances of interest such as cancer cells.

Dr Hudson’s work spans other areas too, including working with industry to develop compostable plastics and ongoing research in opto-electronics. His creativity in applied polymer science was recognised recently with the 8th Polymer International-IUPAC award, organised by SCI, the Editorial Board of Polymer International, and IUPAC (International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry).

We caught up with Zac to ask about these luminous Pdots, compostable plastics, and how it felt to be recognised by his peers.

Dr Zachary Hudson

Tell us about the nanoparticle and remote diagnostic technologies you are developing to boost rural healthcare.

Our group is working with Professor Russ Algar, an analytical chemist at UBC, to develop fluorescent nanoparticles that are bright enough to be detected by a handheld smartphone camera.

The concept is to design nanoparticles that can quantify biological analytes of interest, such as cancer cells or enzymes, and provide a signal that a smartphone can measure. In this way, we hope to create portable, low-cost tools for bioanalysis for use in remote or low-income regions.

Why is the capacity to conduct remote diagnostics so important for those in remote areas?

Coming from Vancouver, I have ready access to sophisticated lab facilities and hospitals that are only a short distance from where I live. This gives me access to some of the world’s most advanced techniques in molecular medicine with relative ease.

For most of the world’s population, however, geography or resources limit their access to these advanced tools that can have a real, positive impact on human health. Expanding access to molecular diagnostic technologies can help more people get the diagnosis they need without a dedicated lab.

How did the ideas for the Pdots come about?

We became interested in Pdots due to Professor Algar’s groundbreaking work using quantum dots for smartphone-based bioanalysis. We learned that by tapping into the versatility of polymer chemistry, we could create polymer nanoparticles, or Pdots, that combined many advanced functions into a single particle.

>> From Covid-19 to the two World Wars, how has adversity shaped innovation? We took a closer look.

How have you worked with other partners to turn these ideas into a reality?

We are currently planning a major initiative with rural health organisations in British Columbia to help move these tools toward practical use. Stay tuned for more info!

You’ve also worked with local industry to reduce the use of single-use plastics. How have you gone about this?

There has been a major push in Canada to reduce the consumption of single-use plastics, and many companies are currently developing new products to respond to this need. Our lab has worked with local industry to formulate and test compostable plastics that can act as substitutes for petroleum-based plastics in consumer packaging.

The Nexe Pod, a fully compostable, plant-based coffee pod created by NEXE Innovations, with Zac as Chief Scientific Officer, received a $1m funding grant from the Canadian government in 2021.

You’ve helped develop compostable materials. How tricky is this from both a material and an environmental perspective?

Compostable plastics are challenging for a few reasons: the demand for them is skyrocketing, so robust supply chains are needed to help companies get away from petroleum feedstocks. The regulatory framework around compostable plastics also varies widely by country, which poses challenges for international commercialisation.

Finally, most machinery for the high-speed manufacturing of plastic packaging is highly optimised for petroleum-based plastics, so new equipment and techniques that are suitable for processing compostable plastics need to be developed alongside the plastics themselves.

>> Do you work in pharmaceutical development? Check out our upcoming events.

What’s next for these innovations, and are you working on anything else interesting?

I've spent most of my career working on light-emitting materials for display technologies and bioimaging, and we’ve recently learned that many of these same materials make useful photocatalysts with applications in the pharmaceutical industry.

We recently partnered with Bristol Myers Squibb to develop all-organic photocatalysts with performance on par with some of the expensive iridium-based catalysts that industry is currently using. I'm looking forward to developing this area further.

What was it like to win the 8th Polymer International-IUPAC award for Creativity in Applied Polymer Science?

It was a great feeling to have our group’s work recognised by the international polymer community. The award lecture at the IUPAC conference also gave us the perfect venue to highlight some of the research directions I’m most excited about in the years ahead.

Those with the blood group O reportedly have the lowest likelihood of catching Covid-19, and the new top-up jab should provide relief against sub-variants of the disease.

By now, most of us have been stricken by Covid, but 15% of people in the UK have evaded the virus. According to a testing expert at the London Medical Laboratory, the great escape is down to three factors: blood group, vaccines, and lifestyle.

Having assessed the findings of recent Covid-19 blood type studies, Dr Quinton Fivelman PhD, Chief Scientific Officer at London Medical Laboratory (LML), believes that people with the blood group O are less likely to be infected than those with other blood groups, while those with blood type A are far more likely to contract the virus.

‘There have now been too many studies to ignore which reveal that people have a lower chance of catching the virus, or developing a severe illness, if they have blood group O,’ he said.

Indeed, research from the New England Journal of Medicine had previously found that those with blood type O were 35% less likely to be infected, whereas those with Type A were 45% more vulnerable. A further benefit of type O blood is the reduced risk of heart disease compared to those with type A or B blood.

>> What is the ideal body position to adopt when taking a pill? Wonder no more.

Staged stock images are not thought to increase your chances of contracting Covid-19.

According to the NHS, almost half of the population (48%) has the O blood group; so, clearly, other factors come into play in terms of our susceptibility. Dr Fivelman said: ‘By far the most important factor is the number of antibodies you carry, from inoculations and previous infections, together with your level of overall health and fitness.’

Tackling the sub-variants

So, those who are more careful about visiting crowded places, who eat well, and are fortunate enough not to have an underlying illness have better chances of avoiding Covid-19. According to LML, having been vaccinated also helps, though these benefits have slowly worn off. That is why the new top-up jab with the Omicron variant could provide some relief for those who take it.

‘The new Omicron jab has come none-too-soon, so many people are now suffering repeated Covid infections,’ he added. ‘That’s because the new Omicron BA.4 and BA.5 sub-variants do not produce as high an immune response as the previous strains, so re-infection is more likely to occur.

‘Higher levels of antibodies are important to neutralise the virus, stopping infection and limiting people transmitting the virus to others.’

>> Which herbs could boost your wellbeing? Dr Vivien Rolfe tells us more.

What is the best posture to adopt when taking a pill, and why does it help your body to absorb the medicine quicker?

Was Mary Poppins wrong? A spoonful of sugar may help the medicine go down, but does it do so in the most delightful way? Not according to Johns Hopkins University researchers in the US.

They say the body posture you adopt when taking a pill affects how quickly your body absorbs the medicine by up to an hour. It’s all down to the positioning of the stomach relative to where the pill enters it.

The team identified this after creating StomachSim – a model that simulates drug dissolution mechanics in the stomach. The model works by blending physics and biomechanics to mimic what’s going on when our stomachs digest medicine and food.

Standing up, on your back, or by your side?

Looks like we’ve got a pro here.

Without further ado, here are the four contenders for taking the pill: standing up, lying down on your right side, lying down on your left side, and swallowing the pill on your back.

>> What’s next in wearables? We looked at a few Bright SCIdeas.

According to the researchers, if you take a pill while lying on your left side, it could take more than 100 minutes for the medicine to dissolve. Lying on your back is next in third, the narrowest of whiskers behind swallowing a pill standing up. This time-honoured method takes about 23 minutes to take effect.

However, by far the most effective method (and, therefore, the most delightful way) is lying on your right side, with dissolution taking a mere 10 minutes. The reason is that it sends pills into the deepest part of the stomach, making it 2.3 times faster to dissolve than the upright posture you’re probably taking to swallow your multi-vits.

Your posture is key in ensuring your body absorbs medicine quickly. Image: Khamar Hopkins/John Hopkins University.

‘We were very surprised that posture had such an immense effect on the dissolution rate of a pill,’ said senior author Rajat Mittal, a Johns Hopkins engineer. ‘I never thought about whether I was doing it right or wrong but now I’ll definitely think about it every time I take a pill.’

Next week, we will investigate more of the medical approaches espoused by much-loved fictional characters, starting with George’s Marvellous Medicine, before moving onto the witches in Macbeth. No one is safe.

In the meantime, you can read the researchers’ work in Physics of Fluids.

What is so special about rainbow chard pigments, and what does this tasty plant have in common with cacti? The SCI Horticulture Group explains all, ahead of their appearance at BBC Gardeners’ World Live in Birmingham from 16-19 June.

The origins of chard

Chard (Beta vulgaris, subspecies vulgaris) is a member of the beetroot family and is grown for its edible leaf blades and leaf stems. Chard, sugar beet, spinach and beetroot have all been domesticated from the same wild ancestor species – sea beet (Beta vulgaris, subspecies maritima). Another food crop from the same botanical family is quinoa.

The term chard comes from the 14th century French word carde, which means artichoke thistle.

Nutritional properties

Chard's leaves are a valuable source of mineral nutrients, with a normal serving of 100g containing: 24% of our daily magnesium needs, 17% of iron, 16% of manganese, and 12% of both potassium and sodium. The same portion can provide 22% of our daily vitamin C needs, 13% of vitamin E, and 100% of our vitamin K.

>> What gives chillis their heat? The SCI Horticulture group has explored the weird and wonderful world of chillis.

The edible petioles (leaf stems) of Swiss chard are typically white, yellow, or red. Lucullus and fordhook giant are cultivars with white petioles. Canary yellow has yellow petioles and red-ribbed forms include ruby chard and rhubarb chard. Rainbow chard is a mix of coloured varieties, often mistaken for a variety unto itself.

The pigments that produce these colours belong to a special group – known as the betalains. These pigments are found only in species of one small section of the plant kingdom called caryophyllales. The pigments in the rest of the plant kingdom have different chemical structures, made up of only carbon, hydrogen and oxygen, whereas the betalain chemical structures also contain nitrogen.

Rainbow chard contains betalains, as do cacti, pokeweed, and (above) bougainvillea.

The many uses of chard pigments

The colourful pigments in plants not only contribute to the beauty of our gardens – they advertise the presence of flowers to pollinators or fruits to dispersal agents. Others deter herbivores by tasting bitter or act as a sunscreen to protect from strong ultraviolet light.

The vivid pigments found in chard are particularly useful. Betanin is the best-known pigment from this group and gives rise to the striking colour of beetroot. It is used commercially as a natural food dye, can help preserve food, and contains antioxidant properties.

Betanin, the pigment that makes beetroot (and poop) red.

Some people are unable to metabolise betanin, which gives rise to a phenomenon known as beeturia – where human waste is coloured red by the betanin.

Cooking with chard

When cooking with chard, it can be treated as two separate vegetables – the leafy part and the crunchy petiole. Blitva is a traditional Croatian dish made from the leafy part, often cooked along with potatoes and served with fish.

Blitva is made with chard, potato, olive oil, and garlic.

Chard stalks sautéed with lemon and garlic forms another popular side-dish, while lovers of Italian cuisine can turn rainbow chard into a pesto with pine nuts, parmesan and basil.

Find us at BBC Gardeners’ World Live

From 16-19 June, the SCI Horticulture Group will tell the public all about the hidden chemistry behind their favourite fruit and vegetable plants at the National Exhibition Centre in Birmingham for BBC Gardeners’ World Live. If you’re curious to learn all about rainbow chard, chillis, and strawberries, pop by and say hello!.

>> Written by the SCI Horticulture Group and edited by Eoin Redahan. Special thanks to Neal Price from Chillibobs, Martin Peacock of ZimmerPeacock, Hydroveg, and The University of Reading Soft Fruit Technology Group for supporting the work of the SCI Horticulture Committee at BBC Gardeners’ World Live.

>> The SCI Horticulture Group brings together those working on the wonderful world of plants.

Which molecules give strawberries their distinctive smell, how are experts using different types of light to grow them all year round, and just how many of them do we eat? The SCI Horticulture Group told us all about this beloved fruit ahead of their appearance at BBC Gardeners’ World Live in Birmingham from 16-19 June.

Where did strawberries originate?

The woodland strawberry (Fragaria vesca) was first cultivated in the 17th century, but the strawberry you know and love today (Fragaria x ananassa) is actually a hybrid species. It was first bred in Brittany, France, in the 1750s by cross-breeding the North American Fragaria virginiana with the Chilean Fragaria chiloensis.

The strawberry is a member of the rose family, as are many other popular edible fruits such as apples, pears, peaches, and plums. It is the most commonly consumed berry crop worldwide.

People in the UK consume an average 3kg of strawberries every year. Perhaps a certain sporting event has something to do with it…

How many do we eat?

A staggering 9 million tonnes of strawberries are produced globally each year, and their popularity certainly extends to UK shores, and not just during Wimbledon. In the UK alone, the average per capita consumption of strawberries is about 3kg a year!

Domestic strawberry production provides almost all the required fruit for the UK market from March to November; and in 2020, 123,000 tonnes of strawberries were produced within the UK.

This stands in stark contrast to the 50,000 tonnes produced in 1985, when UK strawberries were only produced during June and July. Researchers are currently trying to extend the UK growing season to all year round.

She certainly likes the smell of strawberries, but what gives them that distinctive aroma?

What about the chemistry of their distinctive smell?

The characteristic strawberry aroma consists of many different volatile organic chemicals – more than 360 have been observed in fresh strawberries. Which molecules are present, and in what concentrations, depends on the particular cultivar and how mature or ripe it is.

The most common kinds of chemical are furanones and esters. Esters (such as methyl butanoate) account for more than one third of the observed molecules and 25–90% of the volatiles from any one cultivar.

These molecules are responsible for the fruity and floral notes of the aroma. The most characteristic furanone that gives rise to the characteristic strawberry odour is DMHF.

Pictures like this only increase demand for strawberries out of season.

How to produce strawberries all year...

To optimise strawberry growing conditions, researchers are investigating the influence of temperature, photo-period (response to daily, seasonal, or yearly changes in light and darkness), growth hormones, night-break lighting and CO2 enrichment on flowering and fruiting timing, yield, and quality.

Optimal chilling models are also being developed for both June-bearers and ever-bearers. Critically, a careful and detailed evaluation of the environmental and economic costs of producing winter UK strawberries compared to imports is being undertaken.

Extending the growing season in the UK would have a number of benefits, such as; meeting the increasing demand for out-of-season strawberries while increasing food security, reducing food miles, contributing to public health, providing continued employment, and supporting sustainable farming.

>> Are you a keen gardener? Our resident gardening expert, Geoff Dixon, provides plenty of gardening tips for you on the SCIBlog.

Improving the fruit's nutrient profile

The nutrient content of strawberries is dependent in part on the plant’s growing conditions. The interaction between light intensity and root-zone water deficit stress is being examined to improve berry nutrient content. Researchers are also investigating how to apply this to commercial strawberry production in total environment-controlled agriculture systems.

See how a college in Finland is harnessing LEDs to power a vertical strawberry farm!

LED light colour and strawberry growth

Light emitting diode (LED) lighting increases yields in out-of-season strawberry production. LEDs have a higher energy efficiency than traditional horticultural lighting and come in a range of single colours with varying efficiencies and effects on plant growth.

Red LEDs convert energy into light (and drive photosynthesis) most efficiently, followed by blue, green, and far-red, respectively. However, red light alone is not sufficient for optimum plant growth. Blue light controls flowering, promotes stomatal opening (pores found in various parts of the plant), inhibits stem elongation, and increases secondary metabolites (organic compounds produced by the plant), thereby improving flavour.

Additional green LEDs, which appear white, improve visibility for workers. These lights can also penetrate deeper into the plant canopy, improving photosynthesis. Far-red light produces shade avoidance responses such as canopy expansion and earlier flowering, which can be beneficial for increased light capture and earlier fruiting.

>

>Confirmed strawberry.

Who is carrying out strawberry research in the UK?

The Soft Fruit Technology Group at the University of Reading is just one of the institutions providing research to support the UK strawberry industry. The main areas of research are plant propagation, crop management, and production systems.

Find us at BBC Gardeners’ World Live

From 16-19 June, the SCI Horticulture Group will tell the public all about the hidden chemistry behind their favourite fruit and vegetable plants at the National Exhibition Centre in Birmingham for BBC Gardeners’ World Live. If you’re curious to learn all about strawberries, chillis, and chard, pop by and say hello!

>> Written by The SCI Horticulture Group. Special thanks to Neal Price from Chillibobs, Martin Peacock of ZimmerPeacock, Hydroveg, and The University of Reading Soft Fruit Technology Group for supporting the work of the SCI Horticulture Committee at BBC Gardeners’ World Live.

An Artificial Intelligence tool that could change the way we treat heart disease wowed the judges at this year’s Bright SCIdea competition. Now that the dust has settled, we asked Raphael Peralta, from the winning CardiaTec team, about winning the competition, the need for this technology, and tips for future participants. After winning this prestigious competition and coming away with the £5,000 first prize, the future is bright for co-founders Raphael Peralta, Thelma Zablocki and Namshik Han. So, how do they reflect on the story so far?

Team CardiaTec (UK)

Tell us about CardiaTec

Cardiovascular disease is the world’s leading cause of death, and affects countless lives. Despite this, investment and innovation within the space has been severely stagnated, especially in comparison to fields such as oncology. The current treatment landscape remains unchanged, and treatments are most often prescribed in a standardised, one-size-fits-all approach. However, people are fundamentally different, and as shown by the Covid-19 pandemic, similar groups of people can experience a disease in a significantly different manner, and as such it is very important to understand biological processes at a patient level to produce effective therapeutic outcomes.

CardiaTec is leveraging artificial intelligence to structure and analyze large scale biological data that spans the full multiomic domain. This allows for a comprehensive understanding of disease pathophysiology to better develop novel and effective therapeutics for cardiovascular disease.

Casting your mind back to the moment you were announced the winner of Bright SCIdea 2020, what were your initial thoughts?

We thought we had a good opportunity to win it, but obviously when it was announced, it was a great feeling. Winning this competition is a further validation that what we are generating has real world value.

It was a great judging panel, with a breadth of experience across drug discovery and the pharmaceutical industry. We were up against immense global competition and the fact that we won shows that there’s a need for novel innovation in the cardiovascular space to ultimately drive the development of new therapeutics that are going to help change people's lives.

How did you think of the idea? Was there a ‘eureka’ moment?

The way the initial idea came about was through the identification that the cardiovascular space had a massive unmet need compared to other spaces such as oncology. I had worked with a cardiovascular company doing some consulting work and this is where it came to light.

In combination, multiomic techniques are becoming increasingly accessible in line with technological developments, which have made processes of next generation sequencing and proteomic profiling increasingly cheaper. These processes generate large amounts of data, which then lend themselves to applications of machine learning to derive biologically meaningful insights. These process, although becoming increasingly familiar in areas such as oncology, are highly underrepresented in cardiovascular disease, and thus there spans opportunity to develop completely unique and novel insights.

How does the technology work?

Here, CardiaTec uses data across genomics, epigenomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics, to generate novel biological insights with the help of AI and machine learning applications. Taking these many ‘omics’ into consideration is what defines a ‘multiomic’ approach. Biology is complex, and trends require full multiomic assessment to truly understand where dysregulation of specific processes is occurring, to then inform the best means of intervention.

CardiaTec is developing a platform, which with time will grow to become one of the most comprehensive foundations of cardiovascular disease biology. Results and outcomes are iteratively incorporated into the model, and new hypotheses are tried and tested across a range of pre-clinical settings. Collectively, CardiaTec aims to generate novel drug targets that can be used to help reduce the burden of disease in current and future patient population.

In the process of getting to the final, there were several opportunities to engage with entrepreneurs, investors, business leaders, and experts in intellectual property (IP). Can you share key takeaways from these sessions?

One of the most important things you can do is speak to people. Every business starts from an idea. As you start developing, you change and refine the business model. We take every chance to engage with people who have industry experience. It’s really important that we take the advice of these people on board; this is especially true in the field of biotechnology where you take risks across the technology side, the commercial side, and the biological side. It takes a lot of experience to mitigate those risks.

How difficult has it been taking that idea and turning it into a viable business proposition?

Thelma and I came out of the MPhil in Bioscience Enterprise at the University of Cambridge. It gave us this really strong foundation to start building. We also had the biological knowledge from our previous degrees. This framework, where we had key opinion leaders and great people in the field with whom we could bounce ideas off, was the first step. We saw that the idea was really positive and was received well by a lot of people. So, we thought: ‘we’re onto something’.

When building a biotech company, if you’re not passionate about it and don’t want to spend a lot of your time dedicated to the project, then it’s not going to take off. You need to be there to make changes, and really embrace and understand where you believe it’s going to go in line with the advice you've been given and the insights that you have generated.

We’re not only interested in understanding the intricate nature of biology. We’re also interested in how this has real life application in changing people’s lives. Every person we speak to has been affected in some way by cardiovascular disease.

I noticed that your presentation was really polished. Do you have any tips for people presenting in the final?

We’ve presented a lot of times so I think practice makes perfect. With a presentation, you need to be able to tell a story. It’s all about the storyline and building that image. You have to take care and be diligent in the process. Take time to make sure everything is structured correctly and that the story flows. Don’t be afraid to present to a lot of people who will give you advice. Take the time to make the amendments and run it through again and again, and see what the response is. So, take your time on the presentation to get your story across.

You were both very calm when the judges’ questions came. How did you prepare for these questions?

Out of this Cambridge network, the people we spoke to all asked the right questions. You see the pattern of these questions. They all want to know similar things. So, once we identified that pattern, we wrote down the questions that were important from our conversations and we practiced responses to these questions, which were by this point, fully embedded into the company’s business model; which then lends itself to an insightful, actionable response.

How are you going to use the £5,000 prize money and what’s next?

We’ll put the prize money towards refining of some of our technology. In terms of what’s next, Thelma (Zablocki), Namshik (Han), and I are dedicated to this company. We want to see it through and eventually make a drug that ends up reaching patients. This will take a long time.

To see that in the real world, where someone’s getting prescribed a drug that you discovered would be incredible.

>> For more on this year’s Bright SCIdea final, go to: https://www.soci.org/news/2022/3/bright-scidea-final-2022.

We caught a tantalising glimpse of the next generation wearable technology at this year’s Bright SCIdea challenge final.

When we look at our FitBits or Apple Watches, we wonder what they could possibly monitor next. We know the fluctuations of our heartbeat, how a few glasses of wine affect our quality of sleep, and the calories burnt during that run in the park. But what’s next?

If the amazing wearable devices pitched by just three of our Bright SCIdea finalists are anything to go by, then we can look forward to not just next generation health monitoring but possible in-situ treatment too.

Measuring stress and managing diabetes

In recent times, medics have learnt far more about stress and its effect on our health. Indeed, stress was the focus of Happy BioPatch (from Oxford University and Manchester University) technology. The second place team has incorporated an IP-protected enzyme within a patch that measures your stress levels (by detecting the levels of cortisol in your sweat) throughout the day.

This information migrates from body to phone and notifies you if your stress levels are too high. One of many exciting aspects of this technology is that it could be used by physicians to check if patients need treatment for depression and prevent the serious consequences of stress. As one of the judges said, ‘I like it because it’s preventative.’

From mental health to physical health, two of the other finalists use wearable devices to address maladies in in-situ. BioTech Inov, from the University of Coimbra in Portugal, has developed plans for a subcutaneous biomedical device that tracks the blood sugar levels in diabetes patients. This technology would enable the wearer to track their blood sugar levels and let them know if trouble is lurking.

The latest smart watches track your body temperature, sleep quality, and can even detect electrodermal activity on your skin to gauge stress levels. | Editorial image credit: Kanut Photo / Shutterstock

Releasing heat and magnetic fields

Another intriguing development was the in-device treatment developed by the Hatton Cross team (comprising students from the University of Warwick, Imperial College London and Queen Mary University of London). The team is developing wearable technology that can detect wrist pain from sport, or the types of repetitive stress injuries arising from typing or writing too much.

One of the most fascinating aspects of the technology is the potential for in-device treatment. On the preventative side, the device could use vibration to alert users that their wrists are under strain. They also mentioned using heat from the device, or the release of a 0.05 Tesla magnetic field, to relax the muscles.

Another really insightful comment on the technology came from one of the judges. Dr Sarah Skerratt suggested that this type of technology - which is subtly attuned to the movements of the hand and wrist - could theoretically be used in the early diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease or Alzheimer’s disease. That is not to say there aren’t regulatory issues with developing wearable technologies for medical purposes, as the judges pointed out, but the potential of such devices is huge.

Wearable devices could be used to help diabetes sufferers, such as this Insulin Management System used by those with type 1 diabetes. | Editorial image credit: Maria Wan / Shutterstock

The staggering thing is that the technologies pitched by the Bright SCIdea finalists are just three of the myriad innovations being developed around the world at the moment.

Thirty years ago, few of us could have imagined that we would have a personal computer, music system, TV, watch, video, phone, camera, and games console all encapsulated within a single box that fits in our pockets. In 30 years’ time, we will scarcely be able to believe the health capabilities of the devices worn on our wrists and bodies.

Perhaps you will have heard of them first during the Bright SCIdea challenge?

How do flowers use fragrance to attract pollinators, and how do pollution and climate change hamper pollination? Professor Geoff Dixon tells us more.

‘Fragrance is the music of flowers’, said Eleanour Sophy Sinclair Rohde, an eminent mid 20th century horticulturist. But they are much more than that. Scents have fundamental biological purposes. Evolution has refined them as means for attracting pollinators and perpetuating the particular plant species emitting these scents.

There are complex biological networks connecting the scent producers and attracted pollinators within the prevailing environment. Plants flowering early in the year are generalist attractors. By late spring and early summer, scents attract more specialist pollinators as shown by studies of alpines growing in the USA Rocky Mountains. This is because there is a bigger diversity of pollinator activity as seasons advance. Scents are mixtures of volatile organic compounds with a prevalence of monoterpenes.

Environmental factors will affect scent emission. Natural drought, for example, changes flower development and reduces the volumes and intensity of scent production. The effectiveness of pollinating insects, such as bees, moths, hoverflies and butterflies is reduced by aerial pollution.

Pheasant’s eye daffodils (Narcissus recurvus).

Studies showed there were 70% fewer pollinators in fields affected by diesel fumes, resulting in lower seed production. Pollinating insects do not find the flowers because nitrogenous oxides and ozone change the composition of scent molecules.

Extensive studies of changes in flowering dates show that climate change can severely damage scent–pollinator ecologies. Over the past 30 years, blooming of spring flowers has advanced by at least four weeks. Earlier flowering disrupts the evolved natural synchrony between scent emitters and insect activity and their breeding cycles. In turn that breaks the reproductive cycles of early flowering wild herbs, shrubs and trees, eventually leading to their extinction.

The lilac bush, known for its evocative scent.

Heaven scent

Scents provide powerful mental and physical benefits for humankind. Pleasures are particularly valuable for those with disabilities especially those with impaired vision. Even modest gardens can provide scented pleasures.

Bulbs such as Pheasant’s eye daffodils (Narcissus recurvus) (illustration no 1), which flower in mid to late-spring, and lilacs (illustration no 2) are very rewarding scent sources.

Sweetly perfumed annuals such as mignonette, night-scented stocks, candytuft and sweet peas (illustration no 3) are easily grown from garden centre modules, providing pleasures until the first frosts.

Sweet peas are easily grown from garden centre modules.

Roses are, of course, the doyenne of garden scents. Currently, Harlow Carr’s scented garden, near Harrogate, highlights the cultivars Gertrude Jekyll, Lady Emma Hamilton and Saint Cecilia as particularly effective sources of perfume. For larger gardens, lime or linden trees (Tilia spp) form profuse greenish-white blossoms in mid-season, laden with scents that bees adore.

Written by Professor Geoff Dixon, author of Garden practices and their science, published by Routledge 2019.

The clichés we use become so downtrodden that we often say them without thinking. How many times, for example, have you said you went with your gut on a certain decision?

As with many of these aphorisms, there appears to be genuine wisdom behind it. Scientists are learning all the time about the links between our guts and our brains, and recent findings from a California Institute of Technology-led (Caltech) study have added to our understanding of what’s going on behind our belly buttons.

This research contends that a particular molecule, produced by our gut bacteria, has contributed to anxious behaviour in mice. The Caltech researchers say that a small-molecule metabolite that lives in the mouse’s gut can travel up to the brain and alter the function of its cells. This adds further grist to the belief that there is a link between our microbiome, brain function, and mood.

The researchers behind the Nature paper say previous studies found that people with certain neurological conditions have different gut bacteria communities. Furthermore, studies in mice revealed that manipulating these communities can alter neurological states.

>> Curious about which herbs could boost your wellbeing and how they work in your body? Then read our recent blog on this topic.

Their study investigated the bacterial metabolite 4-ethylphenyl sulphate (4EPS) that is produced in the intestines of humans and mice and circulates throughout the body. In particular, they focused on the effect of 4EPS on mouse anxiety. For the sake of the study, mouse anxiety measured the creature’s behaviour in a new space - whether it hid in a new space as if from a predator or whether it was willing to sniff around and explore it.

The researchers compared two groups of lab mice: those colonised with pairs of bacteria that were genetically engineered to produce 4EPS, and a second group that was colonised with similar bacteria that couldn’t produce 4EPS. They then observed the rodents’ behaviour after being introduced to a new area.

Some mice become anxious when introduced to new spaces, and this is reflected both in the gut and the brain.

The results were very interesting indeed. The researchers observed that the group of mice with 4EPS spent far less time exploring this new place and more time hiding compared to the second group of non-4EPS mice. They also found that brain regions associated with fear and anxiety were more activated within this first group.

>> Interested in drug discovery? Why not attend our upcoming event at the Francis Crick Institute, London, UK.

When the mice were treated with a drug that could overpower the negative effects of 4EPS, their behaviour became less anxious. A similar study in Nature Medicine also found that mice were less anxious when treated with an oral drug that soaked up and removed 4EPS from their bodies.

The Caltech-led research could inform our understanding of anxiety and mood conditions.

‘It’s an exciting proof-of-concept finding that a specific microbial metabolite alters the activity of brain cells and complex behaviours in mice, but how this is happening remains unknown,’ says researcher Sarkis Mazmanian, in whose laboratory much of the research took place.

‘The basic framework for brain function includes integration of sensory and molecular cues from the periphery and even the environment. What we show here is similar in principle but with the discovery that the neuroactive molecule is of microbial origin. I believe this work has implications for human anxiety or other mood conditions.’

So, our predecessors were right: there’s a lot more to those gut feelings than you think.

>> Read the Nature paper on the Nature magazine website.

The plant-based meat alternative market is growing rapidly, and cell-cultured meats could be coming soon to your dinner plate once they receive regulatory approval. Gavin Dundas, Patent Attorney at Reddie & Grose, provides his expert perspective on the state of the meat alternative market.

Which is receiving more emphasis based on patent activity: lab-grown meat or plant-based meat alternatives?

Comparing cultivated meat to plant-based meat is a bit like comparing apples and oranges.

Plant-based meat is here - it’s in shops, and it’s in growing numbers of restaurants and fast-food outlets. Even McDonald’s – arguably the world’s most well-known hamburger outlet – released its first plant-based burger in the UK on 13 October 2021: the aptly-named McPlant. The McPlant has been accredited as vegan by the Vegetarian Society, and includes vegan sauce, vegan cheese and a plant-based burger co-developed with Beyond Meat.

Cell-cultured meat is a very different prospect, as cellular agriculture is more high-tech, so companies entering that sector require a higher degree of specialised technical expertise. Companies delving into cultivated meat also require a fair bit of funding, as cultivated meat has not been approved for sale in any country other than Singapore, so it is not yet possible to sell their products to consumers.

The reality at the moment is that plant-based meat alternatives have a huge head-start in the marketplace, while cultivated meat is not yet on sale in most countries. So, for most new companies looking to make money in the alternative protein market, plant-based products are likely to be the easier way to start.

On the other hand, this means that the plant-based meat market is more crowded already, while cultivated meat companies are investing in the hope of getting a bigger share of that market once it matures.

In which food types have you seen a particular surge in patent applications, for example plant-based meat alternatives or lab-grown meat?

Based on searches using patent classification codes commonly used for plant-based meats and lab-grown meat (known as ‘cell-cultured meat’ or ‘cultivated meat’), it appears that there are significantly more patent applications in the field of plant-based meats, but that patent filings relating to cultivated meat are growing more quickly.

Of all the patent publications relating to plant-based meats, 15.2% were published since the start of 2020. Of the patent publications relating to cultivated meats, 27.6% were published since the start of 2020.

This outcome is probably not surprising. Plant-based meats have been around much longer and are now widely established in the market, so many more companies have had time and opportunity to file patent applications for innovations in this area. Cultivated meats are at an earlier stage in their development, but with a large number of new companies having been formed in this area in the last few years, it is not surprising that this has resulted in a high growth rate of patent applications as cultivated meat gets closer to commercial reality.

Beyond Meat’s plant-based meat substitutes have reached the mainstream. | Jonathan Weiss/Shutterstock

How much movement has there been on the equipment and other innovations that will facilitate large-scale meal alternative manufacturing?

There is a huge difference between small-scale production of cultivated meat in a laboratory, and the large-scale manufacturing that would be needed to supply supermarkets and restaurants throughout whole countries and - eventually - the whole world.

Growing meat using cellular agriculture involves the use of animal cell lines to grow animal products in bioreactors, where the cells are immersed in a growth medium that feeds nutrients to the cells as they develop. Over the last decade there have been huge advances in these processes, but as demand for cultivated meat grows there will definitely be continued innovation to improve efficiency and scale-up manufacturing capacity.

Commercial growth medium is currently costly, so the development of more cost-effective growth media is likely to be an area of much research. Another ongoing challenge is the development of high-quality cell lines and scaffold materials that are suitable for high-quality, large-scale production.

Bioreactor design is also expected to be a big area of innovation - up until now, bench-top bioreactors have in most cases been sufficient to meet the demands of cultivated meat R&D, but as demand increases bigger and better bioreactors will be needed. A particular challenge will be to design bioreactors capable of growing thick tissue layers on a commercially viable scale.

While there is scope for innovation in all of these areas, some companies are already ready to manufacture their cultivated meat products on a large scale. Future Meat Technologies, for example, opened its first industrial cultivated meat production facility in June 2021 in Rehovot, Israel - that facility is reportedly capable of producing 500kg of cultivated meat products every day. In November 2021, Upside Foods opened its first large-scale cultivated meat production plant in Emeryville, California, with the capacity to produce 22,680kg of cultured meat annually.

At the moment, however, a lack of regulatory approval is holding back cultivated meat production. While there are a number of companies that apparently have products ready for market, many will be unwilling to plough huge amounts of money into large-scale manufacturing facilities until they have regulatory approval that lets them actually sell their products.

Thinking of filing a chemistry patent in 2022? Here’s what you need to know.

The UK has cutting-edge companies in the cultivated meat field.

Have any innovations or areas of innovation struck you as particularly exciting? If so, could you tell us more about them?

I am a meat-eater trying to cut down on my consumption of meat, due to a mixture of environmental and ethical motivations. So, as a consumer I’ve been very excited to see the arrival of plant-based meat into the mainstream.

I am particularly excited to try cultivated meat once it is approved for sale. Not long ago ‘lab-grown’ meat seemed like science-fiction, so to get to a point where you can go out and buy it will be incredible. So many people are unwilling to cut down on meat because they like the taste, and because their favourite meals are meat-based, so cultivated meat might hopefully give that same experience with fewer of the drawbacks of animal meat.

I am also excited to see the diversity of cultivated meat products. Cultivated meat chicken nuggets and beef burgers are the products that spring to mind when cell-cultured meat is mentioned, but there are companies out there developing cultivated bacon, pork belly, salmon and tuna, to name a few.

What are the chemistry challenges for those creating plant-based meat alternatives? Find out here.

Given what you know about the patent landscape, where do you think the meat alternative industry is heading, and at what sort of pace do you foresee significant change?

I think the meat alternative industry is only going to continue to grow, as concern over the environmental impact of our eating habits is growing, and the quality and availability of meat alternatives is getting better.

The plant-based meat industry is already doing well, and I expect it to continue on its upward trajectory. I expect companies in this field to continue to file patent applications for their innovations, and eventually we might see some of those patents being enforced to safeguard valuable market shares for the patent owners.

Cultivated meat is the sector that seems to be poised for the most significant change. At the moment, the lack of regulatory approval seems to be the thing holding it back, but if that hurdle is removed there are UK companies aiming to get cultivated meats into shops by 2023. The UK is lucky enough to be home to a number of cutting-edge companies in the field, and a recent report by Oxford Economics researchers forecast that cultivated meat could be worth £2.1 billion to the UK economy by 2030.

The idea of cultivated meat is unlikely to appeal to everyone, so I imagine that it will start out as something of a novelty, but I’d expect to see the availability and range of cultivated meat products grow significantly over the next decade.

Edited by Eoin Redahan. You can read more of his work here.

How much soil cultivation do you need for your vegetables? Professor Geoff Dixon explains all.

Cultivating soil is as old as horticulture itself. Basically, three processes have evolved over time. Primary cultivation involves inversion which buries weeds, adds organic matter and breaks up the soil profile, encouraging aeration and avoiding waterlogging.

Secondary cultivation prepares a fine tilth as a bed for sowing small seeded crops such as carrots or beetroot. In the growing season, tertiary cultivation maintains weed control, preventing competition for resources (illustration no. 1) such as light, nutrients and water while discouraging pest and disease damage.

Lettuce and seed competition

The onset of rapid climate change encouraged by industrialisation has focused attention on preventing the release of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere. Ploughing disturbs the soil profile and accelerates the loss of carbon dioxide from soil.

It is also an energy intensive process. Consequently, many broad acre agricultural crops such as cereals, oilseed rape and sugar beet are now drilled directly without previous primary cultivation. An added advantage is that stubble from previous crops remains in situ over winter, offering food sources for birds. The disadvantages of direct drilling are: increased likelihood of soil waterlogging and reduced opportunities for building organic fertility by adding farmyard manure or well-made composts.

Overall, primary and secondary cultivation benefit vegetable growing. The areas of land involved are far smaller and the crops are grown very intensively. Vegetables require high fertility, weed-free soil, good drainage and minimal accumulation of soil-borne pests and diseases.

Frost action breaking down soil clods

Digging increases each of these benefits and provides healthy physical exercise and mental stimulation. Frost action on well-dug soil breaks down the clods (illustration no. 2). Ultimately, fine seed beds are produced by secondary cultivation (illustration no. 3), which encourage rapid germination and even growth of root and salad crops.

Tertiary cultivation to prevent weed competition is also of paramount importance for vegetable crops. Competition in their early growth stages weakens the quality of root and leafy vegetables, destroying much of their dietary value. Regular hoeing and hand removal of weeds are necessities in the vegetable garden.

Raking down soil producing a fine tilth

Ornamental and fruit gardens similarly benefit from tertiary cultivation. Weeds not only provide competition but are also unsightly, destroying the visual image and psychological satisfaction of these areas.

Lightly forking over these areas in spring and autumn encourages water percolation and root aeration. Once established, ornamental herbaceous perennials and soft and top fruit areas benefit greatly from the addition of organic top dressings. Over several seasons these will augment fertility and nutrient availability.

Written by Professor Geoff Dixon, author of Garden practices and their science, published by Routledge 2019.

A sprig of thyme to fight that cold… Turmeric tea after exercising… An infusion of chamomile to ease the mind… As we move with fresh resolution through January, Dr Vivien Rolfe, of Pukka Herbs, explains how a few readily available herbs could boost your health and wellbeing.

The New Year is a time when many of us become more health conscious. Our bodies have been through so much over the last few years with Covid, and some of us may need help to combat the January blues. So, can herbs and spices give us added support and help us get the new year off to a flying start?

The oils in chamomile have nerve calming effects.

Chamomile and lavender