BY DAVID BOTT

There is an old saying that “no strategy survives first contact with the enemy” (though I prefer Mike Tyson’s more descriptive version “everyone has a plan until they get punched in the mouth”!). When we were planning the Flue2Chem project, we drew out a detailed Gantt chart with deliverables, dependencies and deadlines. Sadly, the elapsed time between the last post in this series and now is a vivid example that Mike Tyson got it right.

To recap, the aim of the Flue2Chem project is to collect the carbon dioxide from flue gases and turn it into a simple non-ionic surfactant for use in detergents and other consumer goods – potentially eliminating the need to extract more fossil fuel to make them. Key intermediates are dodecanol and ethylene oxide, but the first step is to capture the carbon dioxide.

What has gone before

The idea of extracting carbon dioxide from flue gases has been around for a long time, and has actually been “practiced” since the 1950’s. For a long time, it has been driven by the idea that carbon dioxide emissions can be captured and stored underground, thus avoiding adding them to the atmosphere and causing climate change. Nowadays, if you go to a Carbon Capture Utilisation and Storage (CCUS) conference, the few talks on utilisation mostly talk about the direct use of carbon dioxide either in fizzy drinks or for pumping into greenhouses as a feed to horticulture. We are aiming for something different.

The first need is for a source of flue gases. When we were putting together the Flue2Chem consortium we understood that different sources would have different chemical compositions, so we sought out different types of sources to maximise the spread of data for both the techno-economic and life cycle analyses. There are two paper companies in the consortium, Holmen and UPM. Their carbon dioxide emissions are classified as “biogenic”. Both have biomass combined heat and power plants, built in the days when biomass was regarded by the government as a renewable power source, and subsidised under the renewable obligations scheme that formed part of the 2009 Renewable Energy Directive. They each generate about 1000-1500 tonnes of carbon dioxide a day.

We also had the Port Talbot site of Tata Steel as part of the project. You could classify the carbon here as “used fossil carbon”. Coal is used both as a source of heat and as a reducing agent to turn the iron ore into iron. It is a complex process and so there are many sources of carbon dioxide on the Port Talbot site, some mixed with carbon monoxide In total, they generate about 15000-20000 tonnes of carbon dioxide a day.

The basic requirement for a process to capture carbon dioxide is easy to state – you need a system that will reversibly absorb carbon dioxide, and some good engineering!

The liquid amine route for capturing carbon dioxide uses a mixture of amines to react with the carbon dioxide to form carbonates. The absorption is usually carried out in a vertical column where the amine trickles down in a packed column and the carbon dioxide flows up. The resulting carbonate is then moved into another column where it is heated to decompose the carbonate to reform the amine and release the carbon dioxide. The energy efficiency of the process is largely determined by the energy required to decompose the carbonate. Over the years, different companies have optimised their mixture to minimise the energy costs and often keep this as “black art”.

Solid state absorption systems rely on physisorption. They used to be based on zeolites, but many recent ones use metal-organic frameworks. The early ones used a similar temperature driven process to control the absorption and desorption, but there are now systems based on pressure swing, where the absorption is driven by higher pressure and the desorption by much lower pressures. These are suggested to use lower energy than the more conventional temperature driven systems.

So, how is it going?

Early on in the project, one of the two companies providing the capture systems we wanted to include in the project – Carbon Clean – ran into an issue with the Environment Agency’s policy regarding solvent disclosure. They use an amine based solvent and, as mentioned above, they want to protect the confidentiality of their IP from this major commercial risk. However, the Environment Agency requires disclosure of any chemicals that might be emitted in any process, and most amines have a measurable partial pressure at the temperature used in the carbon capture process, so although they might have been able to get an exemption for a research or test use, once they go commercial in the UK with their system, they will have to disclose to the Environment Agency. AND, the Environment Agency is subject to Freedom of Information requests and would have to disclose Carbon Clean’s proprietary information. This is why Carbon Clean chose to withdraw its technology from the project, while continuing to provide techno-economic analysis.

This led to another decision – this time by Tata Steel. They had already worked with Carbon Clean in India and were looking to scale up the technology to the 10 tonnes/day envisaged within the project. With that off the table, they wanted to rethink their plans. As they were doing so, the bigger announcement that they would close the blast furnaces and move to use electric arc furnaces at Port Talbot amplified their concerns. Depending on the exact implementation route they choose, there might be minimal emission of carbon dioxide, so they withdrew from the work package to collect carbon dioxide.

Fortunately, in addition to Carbon Clean, we had also included a solid state capture technology, albeit at a much lower state of technology development, in the project. FluRefin had been developed at the University of Sheffield and was being commercialised by Carbon Capture and Utilisation International (CCUI). This had been operated at the small scale but as part of the project, it was being scaled up to 1 tonne/day capture. This required wholly new equipment, some of which had to be imported from India, some from Germany, but was assembled in the UK. It was planned to be installed at the first collection site (Holmen) at the end of November 2023, was actually delivered to site in mid-January, but commissioning issues delayed the first real carbon capture until late April. We have learnt a lot about fast-tracking process development – and the challenges it causes, partners working off different versions of the Process and Instrumentation Diagrams, the design experts being in Sheffield and the equipment being in Workington and so on but, as anyone who has done this before will tell you, this is all quite normal and we were very optimistic in our initial plans! Once on site in Workington, we had the support of some excellent engineers and the various problems were overcome.

One aspect of using a pressure swing process is the need to compress the input gas. This required the use of a number of compressors, but when they arrived we discovered that they had been designed for compressing air to be used as “compressed air” and were a bit “leaky” on the input side. We knew this because the output carbon dioxide concentration was lower that the input and not as we needed and thought we would get. This required more engineering to adapt the compressors for our use.

Another requirement of using the pressure based system is that the input flue gases need to be cooled (from about 150oC to around 30oC) – this recovers a fair amount of heat. More engineering was required!

Over the next few months, we started to capture enough carbon dioxide to supply the chemical conversion work packages. But this led to another “challenge”. We are aiming to capture about 1 tonne per day. This is below the level where we could engage one of the major gas product companies to provide bottling technology, and we were initially not planning to liquefy the gas (so did not have the required equipment). This means we were using a fairly basic “put gas in a pressurised gas bottle” process. Luckily, the University of Sheffield team were also involved in another UK Research & Innovation (UKRI) project – called SUSTAIN Steel. They had a small carbon dioxide liquefaction kit. We have “borrowed” it and are using it to liquefy the captured carbon dioxide, albeit at a very slow rate. We have other ideas for how to do this at a larger scale, but this works, and we are now capturing the required amount of carbon dioxide to send to the two centres where the next stage of our supply chain – the conversion of the carbon dioxide to ethylene oxide and dodecanol – will be carried out, but that’s another post!

So, what have we learnt?

Firstly, that project plans written in a hurry to fit within the proscribed timescale and budget will almost certainly be too optimistic and liable to require drastic adjustment. This was no real surprise to those who had been involved in scaling up processes before, but we rediscovered the saying that “if it can go wrong, it will” is irritatingly true. However, the capabilities of the individual organisations in the project and the creativity of the combined “leadership team” means that we have always found a way out of every “challenge”. We have also applied to Innovate UK to extend the project by 4 months, and have been successful, so have bought a little more time. The next work packages, which would have been squeezed by the 6 month (or so) delays will be “less” squeezed.

Perhaps the biggest learning is the need for flexible resources to enable scaling up the sort of processes we are using. This does not necessarily mean expensive new buildings or plants. A small carbon dioxide liquefaction plant that could handle 1-10 tonnes a day would have saved us about 2 months. More engineering expertise in the consortium might have saved us another couple of months building and commissioning the FluRefin plant. We had some allowance for creep in the original plan but when every month the deadline slipped by a month, I felt sorry for the project manager!

What has really been driven home to us is that the change we are attempting to prove – that it is feasible to move the chemistry supply chain away from virgin fossil carbon as a feedstock – may be scientifically credible, but reducing anything from theory to reality is harder than we think and required even more planning and effort than we imagined.

And we need to use realists, or even pessimists, as planners!!

Written by David Bott, Director of Innovation at SCI and originally published on Linkedin

BY DAVID BOTT

Science is hard work. Understanding the world around us well enough to predict the behaviour of everything from sub-atomic particles to planets requires insight, patience, imagination and rigour. But science also lays the foundations of many of the industries that have changed our world – from pharmaceuticals to airplanes.

It is this application of science to address societal challenges that benefits people. And one of the biggest challenges is moving away from using virgin fossil carbon to feed the chemical supply chain!

It is worth stating at this point that, as we have talked about this work, we meet many people who do not understand how the chemistry using industries underpin other supply chains. We have had to explain many times to disbelieving audiences that cleaning products are currently mostly made from oil!

At the moment, the many branches of the chemistry using supply chains start with about 2.6 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent produced from oil and gas extracted from the fossil reserves (about 5-6% of the carbon extracted annually goes into this use). There are other sources of carbon and the science to use them is proven, but we need to start development and implementation. This means designing and building manufacturing capacity that operates efficiently to produce the volume of material needed to satisfy the current and future market needs – and this is a lot!

Technology, Development, Innovation – whatever you call the process of turning science into products is also hard, but in a different way. Something may be scientifically possible, but to make a product out of it for less than the price people will pay for it and at a volume that all the people that want it will be satisfied can be difficult. And competing with an established route where the feedstocks are cheap and easily available, and the processes have been optimised and scaled over decades, requires tenacity.

Flue2Chem is an Innovate UK funded consortium of 16 organisations that could make up a wholly new supply that produces the materials we currently use at a large scale but without starting from virgin fossil carbon. Rather than trying to do everything all at once, it is focused on a single product – a surfactant that is widely used in a range of cleaning products. It is one way to re-imagine the future of those parts of chemistry based industries that currently use virgin fossil carbon as a feedstock. The project is focused on demonstrating that carbon dioxide can be collected from flue gases and, by a series of chemical steps, turned into that common surfactant. Although it is focused on a single product, the processes and the learning from scaling them up could be applied more widely.

Flue2Chem consortium members

The challenge of scaling-up

Making a lot of anything usually involves making it in a large factory – and the more product needed to satisfy the market demand, the larger the factory. We are mainly talking about chemistry here, so the core manufacturing unit is a reactor. In the laboratory, most people think that chemistry is done in test tubes, but the truth is that the most common reaction vessel is probably a sub 1 litre round-bottomed flask. This is where the science of the basic reactions is tested and optimised. The next step is then a vessel between 5 and 25 litres in size. This is where we first encounter scaling laws! If we make a reaction vessel which is twice as big in the linear sense, it has 8 (23) times the volume and 4 (22) times the surface area. Most chemical reactions involve either the absorption or emission of heat – the amount of heat (absorbed or generated) increases with the volume of the reaction, but the heat must move through the walls of the vessel. So, a reactor three times as big (the 1 litre to 25 litre example above) generates or absorbs 27 times the heat but it must move through 9 times the surface area. The reactor surfaces must be three times as thermally conductive to allow this. The 25 litre flask is often exactly the same design and made of the same material as the 1 litre flask, so this does not happen!

Given that chemical reactors can have a capacity up to 1,000,000 litres these are substantial size differentials! Here the ratio between the initial reactor and the final, at-scale reactor means the challenges for this simplest reaction parameter must change 1000 times.

And thermal management is not the only challenge. Mixing also requires more energy at larger scales; removing the by-products of the reaction is also more problematic as reactor size increases.

But working at large scale has some commercial advantages – the cost of capital equipment needed usually scales at a lower rate than the science gets hard, and the complexity of the ancillary equipment can also be optimised, making larger factories more commercially attractive. Since big factories are often more commercially attractive, the technological challenges have been worked on for decades and large reactors for the currently used reactions are well optimised!

This optimisation, or scaling-up of the process nearly always goes in steps, and the size of those steps depends on the confidence of those in charge! These days, a lot of these steps can be carried out using computer based process software – decades of scaling things up has given industry experience of and insight into the critical factors that need to be considered, but moving to new reactions means the basic information must be measured again!

And this is just to get it to work!

But how big should you make it? An important factor in determining the size of the reactor is the size of the market – and therefore how much product you need to make.

So, how much do we need to make to prove this new supply chain will work?

For most people, the scale of the chemistry based industries are not even recognised, let alone considered.

At present the petrochemicals industry, which provide the bulk of feedstocks to the chemistry based industries globally uses about 2.6 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent a year. To give an idea of scale, if all that was made into polyethylene (commonly used in packaging, toys and cars) it would be a cube just under a kilometre along each length.

As already described, the target molecule of Flue2Chem is a simple surfactant with a chain of 12 carbon atoms as the oleophilic (the bit that attaches to the dirt) end and 5 to 7 ethoxy units as the hydrophilic (the bit that dissolves in the water) end. It is widely used for all sorts of cleaning products – globally figures of around 17,600,000 tonnes a year are quoted. This is equivalent to about 44,000,000 tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent – so about 1.7% of the global petrochemicals market! What sounds a lot rapidly becomes small when you look at the actual numbers!

And how is it playing out for the Flue2Chem supply chain?

When we started the project, we had two carbon capture streams – an established liquid based system capable of collecting 10 tonnes/day and a start-up solid state system with a capacity of 1 tonne/day. Given that we also had three sites from which to capture carbon dioxide and the plan was to run each for 30 days, that would have given us an input of just under a 1000 tonnes of carbon dioxide.

At the other end of the supply chain, the final assembly of the surfactant could be carried out at about 1000 tonnes and the consumer products companies could use all that output to carry out test marketing of at least three products.

We rapidly discovered that the bottleneck would be the chemistry to turn carbon dioxide into ethylene oxide (for the hydrophilic end of the surfactant) and dodecanol (for the oleophilic end). The thermo-catalytic routes might be able to make about a kilogramme of the ethylene oxide and probably much less of the dodecanol. And on the biotechnology side of the options, although there were companies making ethanol (a precursor to ethylene oxide) from flue gases, they were not using carbon dioxide as the source. Biotechnology routes are often attractive because they make a single product, but using the biobased route to dodecanol looks like it would be hard to make even a kilogramme.

This would give us a few problems, but as the project progressed, we ran into another challenge. The company with the liquid system decided to withdraw from active carbon capture in the UK (the subject of a later blog), and one of the carbon sources got a government grant to radically overhaul their plant to drastically lessen the amount of carbon dioxide they might produce, so they have “paused” their direct involvement in that part of the project. We had now gone from a capacity of 990 tonnes to 60 tonnes. This was still more than enough to keep the chemists happy, but it gave us another opportunity to be innovative. The two carbon dioxide sources were in Cumbria and North Ayrshire, but the chemistry to convert it was being carried out in Sheffield and Germany and the biology in North Yorkshire. How could we transport that amount of carbon dioxide? At about 1000 tonnes, it might have been possible to “rent” a bottling facility and install it at the capture sites. At less than 100 tonnes, the equipment did not even exist! The solution we are adopting is to pressurise about 3 kilogrammes of carbon dioxide in pressure vessels and transport it from site to site. This limit on how much carbon dioxide we can transport from the emitters to the converters puts another size restriction in place, so a sizable fraction of the carbon dioxide we capture will have to go back into the flue! This is not ideal, but given the goal is to validate a wholly new, more sustainable supply chain and the lack of any other options, we don't have much choice.

There will be more…

Stepping stones to wisdom – what have we learned?

Perhaps we should have checked our numbers before we submitted the proposal, but since any scale-up project is designed to see how difficult it is to scale-up, discovering that there are issues beyond the technological is good learning.

The chemical and biological restrictions are a result of the lack for scale-up facilities in the UK, and we currently have no other options. If we are to develop the new chemistries required to switch feedstocks away from virgin fossil carbon to carbon dioxide, waste biomass or recycled plastics and oils, we will need several levels of scale beyond those currently available.

Underpinning this last point is the fact that many do not understand how the chemistry using industries underpin other supply chains – even their own. We have had to explain the range of products made from virgin fossil carbon (IEA figures are plastics packaging 36%, upholstery, carpets and paints 16%, textiles 15%, home and personal car products 10%, pharmaceutical and agricultural products 11%, car interiors and tyres 7% and electrical 4%) many times and often find ourselves trying to convince disbelieving audiences that cleaning products are currently made from oil! This means that many in government do not see the need to invest at the national scale in them in a coordinated manner. Scaling-up chemistry is generally not well catered for.

Written by David Bott, Director of Innovation at SCI and originally published on Linkedin

BY DAVID BOTT

There is much talk of “decarbonisation” these days, and you could be forgiven for thinking this means eliminating carbon from all human activities. But there are lots of things that need carbon to exist. The chemistry of carbon is unique and nature relies on it for many things. Carbon has direct influence on conditions for life on our planet, whether or not you factor in the specific needs of human beings! And we depend on carbon chemistry for life too – our bodies burn carbon based fuels ourselves (grains, vegetables and meat are all carbon based materials).

We have also depended for millennia on carbon-based materials as clothing (skins, cotton and wool), housing (wood and thatch), and much more – until about 6000 BC when we started using inorganic materials (metals!) as well. With the birth of the oil age in the late 19th century, we started to make synthetic materials, initially striving to reproduce the properties of the natural materials we were used to – polyester was a cotton like material, polyamides were meant to be like silk, polyacrylonitrile was similar to wool in properties. In healthcare we started making naturally occurring therapies (like aspirin and morphine) at scale using synthetic chemistry. As we understood the relationships between chemical structure and properties during the 19th century, we moved on to more complex chemical structures. We cannot get away from carbon because so many planetary systems depend on it, so getting it rid of it altogether is not really an option!

So, what do we mean when we say “decarbonisation”?

The problem is not with carbon dioxide as such, but with the amount we have put into the ecosphere over the last 150 years or so years and the effect it is having on the climate.

In the past there was a lot more carbon than we currently have in the atmosphere – somewhere between 15-30 times as much – but then life wasn’t the same in the Mesozoic period – evidence suggests the average global temperature was 10-15 degrees higher, so species like us would probably not have survived. Over the intervening 150,000,000 years, a variety of natural processes absorbed and sequestered that carbon in rocks, coal, oil and gas. But coal, oil and gas are an easily available source of energy, and their extraction has powered progress over the last 200 years! And when we burn them, the carbon that was previously safety locked up in the ground goes back into the atmosphere.

So what is the problem?

The amount of carbon dioxide we have generated over the last 150 years can be found in the atmosphere, the oceans and on land. This is the product of the coal, oil and gas we have extracted and burnt over the same time period. The problem is that the Earth’s climate cannot cope with this increase, and we need to stop.

Here is how it all adds up:

Atmosphere – Since the beginning of the industrial revolution, the amount of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere has increased from around 2.2 to 3.3 trillion tonnes – meaning we have added about 1.1 trillion tonnes.

Oceans – There is a lot of focus on carbon dioxide in the atmosphere and the impact it has on climate, but carbon dioxide is also absorbed by the oceans, where it also has an impact – the water becomes more acidic and damages marine ecosystems. For every tonne of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere there is about 0.75 of a tonne in the oceans. This means there is probably about 800 billion tonnes in the oceans.

Land – There is also work that indicates that about 8.3 billion tonnes of plastic waste have been produced since 1950 – roughly equivalent to 26 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide. Since plastics account for about 30% of the petrochemical products stream, we can work out that 87 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide from the use of oil and gas as a feedstock is also in the ecosphere.

Total – This means we can estimate that we have put about 1.99 trillion tonnes of carbon dioxide into the ecosphere since we started using coal, oil and gas as a source of energy.

The amount that we find in the ecosphere is almost identical to the amount extracted from the geosphere over this time period. Evidence that this is a man-made effect can be seen by comparing this number to the 2.2 trillion tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent that industry records show the coal, oil and gas industries have extracted from the planet over the last 150 years. The small difference is probably due to the accuracy of the figures, which have been collected over 150 years!

We often fall into the trap of differentiating between fossil carbon and biogenic carbon, as if biogenic carbon is acceptable, but we have been putting fossil carbon into the atmosphere for so long that it makes up about 35% of the carbon in the atmosphere and has therefore been absorbed by plants and will make up roughly the same fraction of what we call biomass! This means that 35% of the biogenic carbon is really second generation fossil carbon. This becomes important when one source is favoured over another by regulations.

The goal is not to stop using carbon – it is to stop taking it out of the ground and putting it into the ecosphere!

If the various government promises to achieve Net Zero are kept and we do manage to stop using fossil carbon as a fuel by 2050, where will we get the carbon we use as a chemical feedstock that we have come to rely on as the source of materials such as plastics, fertilisers, packaging, clothing, digital devices, medical equipment, detergents or tyres? Currently we use about 2.6 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent a year to make a wide variety of things – through a “petrochemical” supply chain. We cannot “decarbonise” that without inventing new materials to deliver all of the products, but we can “defossilise” it – which means we stop using virgin fossil carbon as its feedstock.

Where will the carbon come from then?

There are three sources of carbon (biomass, recycled plastics/oils/solvents and carbon capture and utilisation) widely touted as replacements for all that fossil carbon. All are essentially recycling previously used carbon. They tend to get framed as competitors for the role, but if you analyse the amounts available, the likely costs of using them, and the timescales needed to get them to the right scale it looks like we will need them all!

Back to Nature

Biomass refers to using biological sources for the raw materials – wood, crops, animals and bacteria are good examples. Advocates rightly point out that many synthetic materials are clones of natural materials. They tend to forget that society moved to synthetic analogues because there wasn’t enough to satisfy societies needs in terms of volume and price, but global supply chains were less sophisticated back then.

However, from the generally accepted numbers, there would be enough raw materials – the planet produces about 50 billion tonnes of biomass a year – of which about 14 tonnes is produced by man. Of that, it is estimated that about 1.8 billion tonnes of “waste” is produced a year – mainly cellulosic. This produced in farms and food processing plants. Of the biomass that goes to food, we waste about 30-40%, so can add another 1.6 billion tonnes, but this is produced in restaurants and houses, so collection might be expensive! And finally, we have the waste we humans and our animals directly produce. Estimates vary but are usually about 500 million tonnes of human waste and almost 3 billion tonnes from farm animals! There would be enough carbon in biomass to satisfy the requirements, but the logistics of collecting it might be a challenge (and probably involve the generation of more carbon dioxide – there is always a trade-off where transport is involved). Also, biological processes can often be slow and less atom efficient than the currently used chemical processes, but this can be accommodated by appropriate systems design.

Nevertheless, the use of biomass as a feedstock for chemicals is already here and growing in scale.

Second time around

All the carbon that currently goes out in the form of products could form the basis of a different recycling route – often called “chemcycling”. Here the previously used plastics, oils and solvents can be partially broken down into reactive chemical species like those used in the manufacture of the original products. This is usually done with heat, and so costs energy. It also often uses solvents or extra chemistry. Given the range of materials that will make up the input, there will probably need to be a sorting process at the front end. And, like the waste biomass, the input materials will be collected from geographically distributed sites, so will need to be transported to plants where the recycling will take place (with the potential carbon dioxide emissions as a result).

Mining the problem

Finally, we could use the largest source of carbon already in the ecosphere – the carbon dioxide we have been putting into the atmosphere. With its current concentration of about 0.05%, it is a daunting task. However, we can “practice” how to make it work with a higher concentration (often 10-15%) – when we burn things, we produce a gas stream with a higher concentration of carbon dioxide and send it up a chimney or flue. We will probably go on burning things for a few years yet and using them as a source of carbon will not only moderate the amount we put into the atmosphere in the short term, but also enable us to refine the technology so that we can one day we can remove carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and reverse the damage we have done to the climate – although sadly it would take hundreds of years to do so.

Are we there yet?

All three routes to providing a non-virgin fossil source of carbon are being worked on already. However, they are all at such a small scale it is difficult to judge their efficiencies and effectiveness.

- Biomass is probably the most technologically advanced, but scaling-up the processes and addressing the collection and logistics issues are important challenges that need to be overcome.

- Recycling the “second generation” carbon cannot supply enough – it is limited by the efficiencies and costs of all the processes from collection to chemical recycling but can probably contribute a sizable fraction of the requirement.

- Carbon Capture and Utilisation (CCU) is the least well advanced but with a roadmap to Direct Air Capture (DAC) (the slightly different name for capturing the carbon dioxide direct from the atmosphere) offers the most compelling argument for investment – if DAC can be made to work commercially, it can be used to remediate the atmosphere. Net zero targets aim to take us back to 1990 levels of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere by eliminating the use of fossil fuels. Depending on the scale and speed at which DAC can be implemented, it might be possible to get back to pre-Industrial Revolution atmospheric carbon dioxide levels in several hundred years!

Carbon Capture (CC) has rather had its reputation tarnished by the pervasive suggestion that it can be used to capture (and store) carbon dioxide so effectively we can go on using fossil fuels for many years. Most analysts outside the oil and gas industry do not see how the maths works!

All of the routes are years away from making a major contribution to replacing the volume of carbon based feedstocks used to make the wide variety of products (and the market is growing at over 5% per year, which means that it will double in size every 12 or so years). We need to start soon and grow quickly to make any meaningful impact.

Written by David Bott, Director of Innovation at SCI and originally published on Linkedin

BY DAVID BOTT

One of the questions we often get asked is ‘how did you assemble such a large project so quickly?’ The short answer is ‘we didn’t, it took years!’, but the story is important

In the last blog we discussed the scale of the use of petrochemicals to make things society doesn't know are made of fossil carbon, and the drive to change this – this time we will look at how we built the team.

On page 17 of the Chemistry Council Strategy published in 2019, you will find the phrase ‘Sustainable Materials for Consumer Products’. This is (we think) the first time the phrase was used in this context,. and so was effectively the beginning of the story.

Technically, there is prehistory. The UK government had tried twice before to understand and support the “chemistry-using” industries but had failed to capture the breadth and scale of their impact on the economy in their engagement. They had included the pharmaceutical companies alongside the more traditional “chemicals” companies, but not the extensive downstream activities that used chemicals to deliver a product or process. In 2018 they had spread their net a bit wider and included the consumer companies who use chemistry to make a large number of products for a whole range of markets. These companies were seemingly more aware of the way consumers were looking at the discussion on climate change and who were wondering why the products they could not live without had to be made from fossil carbon and contribute to climate change. So, these companies started making commitments to be fossil carbon free by 2030 or not long after. The scale of their production (often millions of tonnes) meant that the necessary changes to their supply chains had to be at a similar scale and they quickly found that their suppliers (and their suppliers) could not easily accommodate the changes they wanted to see in their chosen timeframe. What was required was a more radical rebuilding of their supply chains.

The Society of the Chemical Industry (SCI), who were responsible for the Innovation Committee of the Chemistry Council, decided to build a community who could do something about this challenge.

The first workshop in the area was held at SCI on 22 February 2020. It included participants from retailers (Marks & Spencer, Sainsbury’s, Walgreens Boots Alliance and Enkos), consumer products manufacturers (Unilever, GSK, Reckitt Benckiser and Proctor & Gamble) a number and variety of chemical manufacturers (Croda, Innospec, Johnson Matthey, Thomas Swan, BASF, INEOS, Lubrizol and Synthomer), universities/RTOs (CPI, University of Bath and University of York) and several companies engaged in the recycling of materials (Biffa, Symphony Environmental).

The discussion was outcome-oriented, and we finished the day with a draft list of things to work on in the second workshop. But within a few weeks COVID happened and we went into lockdown! As they learned to cope with Zoom and Teams, the core team met online and developed the ideas from the workshop. First, the tasks were sorted into three main buckets – engagement, new chemistries and measurement.

Talking to people

Under the engagement banner, we recognised the importance of explaining what we understood were the challenges and how best to address them. Audiences would include chemistry-based companies in the supply chain, regulators and policy makers in government, and consumers. Initial attempts at engagement rapidly taught us that before we could explain what we were doing, we often had to make the audience aware of the ubiquity of carbon-based chemistry in everyday life and the relationship to climate change. One example was when I found myself being interviewed by Rachel Johnson on LBC about the impact of laundry on climate change and her not believing that the cleaning products themselves were made from fossil carbon resources!

The idea of starting with awareness raising, moving on to (gentle) discussion of the science and technology before even mentioning the “ask” became our approach!

Changing the way we do things

The new chemistries banner was an area where we were all more comfortable. If we were to avoid using fossil carbon as a feedstock, we needed another source of carbon, or we needed to find the functionality the businesses needed using another element. The second option looked very difficult – and therefore expensive. The options for the first were well known – “biomass” (ill-defined but very popular as a choice), recycled (second generation?) plastics and oils (logistics is the current issue) and carbon dioxide (lots of it about, but more energy needed to get it to a useable state).

Then we agreed (being mostly from business) that we needed a specific target at focus on.

If we could start with a non-fossil source of carbon and turn it into a useful molecule, we would have demonstrated that there was a completely different way of making things. In the process we could learn what was possible, what impact this alternative would have on the environment, whether it was commercially viable and what social impact it might have.

Since there are so many things made of fossil carbon – packaging, paints, adhesives, textiles, carpets, upholstery, tyres, drugs, fertilisers, insulation and cleaning products – selection was difficult, but the team knew a lot about cleaning products, so we started there. After a lot of swapping of anonymised data, we alighted on non-ionic surfactants. They are extensively used in consumer cleaning products (about 1,000,000 tonnes a year) and they are relatively simple molecules. These are made up of a hydrophobic end (usually a 12-14 carbon atom chain) and a hydrophilic end (usually made up of 5-7 ethylene oxide units).

Alongside the search for a way to make this sort of chemical without using fossil carbon, we realised that cleaning products were almost invariably flushed down the drain – and that often that meant straight into streams and rivers. We knew from other studies that they would degrade into other chemicals, and eventually into carbon dioxide – but we could not find any studies that mapped the complexity of that degradation pathway – was it a biological process, or was it photolytic, or a mixture of both? We talked to BBSRC. We talked to NERC. To date we have not been able to interest any UK funding agency in researching this aspect of what happens to these carbon based molecules in the environment, although there is lots or research into the effect of the chemicals on the environment!

Measuring what was going on

The third area we pondered over was how to measure what was going on – both currently and as a result of anything we might do. We looked at various life cycle analysis studies and quickly realised there were real differences between academic studies – and even consultancy or in-house techniques. Given that we knew we would be building a wholly new supply chain, how were we going to measure the impact of our actions?

Getting on with it

We knew better what we had to do. The next problem was to find a way of funding the work. It took almost a year of talking to the KTN and Innovate UK before we became aware of the Transforming Foundation Industries competition. In the late Summer of 2021, we decided to develop a proposal to turn carbon dioxide from flue gases into our target surfactant.

The specification of the competition meant that we had to work with other foundation industries. Given that we wanted a source of carbon dioxide, and they mostly produce it, this gave us options. We built links to paper companies such as Holmen and UPM. They often use biomass boilers as heat and energy sources. These are currently classed as zero emissions under the emissions trading scheme, but the rules are tightening and are looking for the next technology to remain viable. We also talked to Tata Steel, who use coke both as a fuel and reducing agent in their blast furnaces. We tried to talk to cement manufacturers but were unsuccessful.

Next, we needed a means to capture the carbon dioxide in their flue gases. There are basically 3 ways to capture carbon dioxide, solvent adsorption, solid phase adsorption and membranes. We contacted Carbon Clean (who use solvents) and were already talking to the University of Sheffield (who were developing a solid phase process). Both were interested and so joined the consortium.

Turning carbon dioxide into the C12 fatty alcohol (to make the hydrophobic end of the surfactant) and the ethylene oxide (to make the hydrophilic end of the surfactant) was the next goal. The BASF, University of Sheffield and Johnson Matthey all had expertise in thermo-chemical processes which could achieve this and all were interested. We knew there would be biochemical processes that could achieve the same goal but no companies in the UK, so we turned to the Centre for Process Innovation (part of the High Value Manufacturing Catapult) and found they were working in the area so added them to the consortium.

Croda were already the supplier of choice to react these two components together to make the final surfactant.

We then had the consumer product companies, Unilever, Proctor & Gamble and Reckitt, who would evaluate the surfactant and “prove” that getting the carbon from a different source did not change the properties.

We also folded in our concerns about measuring the impact of what we had done by including the UKRI Interdisciplinary Centre for Circular Chemical Economy to evaluate the life cycle and technico-economic aspects of the various processes we were evaluating so that we could put together a justified case for a new supply chain at the end of project.

The Confederation of Paper Industries also joined to be able to understand what we had done and recommend it to other paper companies.

And the SCI joined to help with exploitation and dissemination as the project progressed.

Are we there yet?

We submitted our Expression of Interest to Innovate UK just before Christmas 2021 and (mostly) didn't worry about it until the New Year. On 10 January, we learned that our application was successful, so buckled down to writing the full application.

The consortium submitted its proposal on 6 April 2022

As we understand it there were eight proposals submitted but only money for four, but we were still disappointed that the initial funding announcement did not include us! However, somehow Innovate UK found some more money and the remaining projects were judged to be fundable so on 14 July we learned that we had the money!

For those who haven’t applied for Innovate UK funding before, the detailed process is simple but rigorous. One really, really important step is for every company to sign a “Collaboration Agreement”. This sets out the goals of the project, how it will be managed, and how the intellectual property that arises during the project will be allocated. It is often a source of contention, and the amount and intensity of the contention seems to scale geometrically with the number of partners in the consortium. Given that many of the partners were more used to competing than collaborating and they all had lawyers, it seemed at times to scale exponentially! However, because the scientific leads in all the companies had worked together (some, at this point, for over 3 years) and there was real commitment to get started, (after a small hiccup) we all signed the agreement just before Christmas 2022. It was then that we discovered we all had to sign the Grant Offer Letter as well, but we managed that too.

Then the work started…(see Part 3)

The exam question

So, how did we assemble the consortium?

- It took time, and lots of interaction. The core of the consortium – Unilever, P&G, Reckitt, Croda, BASF, Johnson Matthey and the SCI – had all been sharing ideas, challenges, opportunities and frustrations for over 3 years. Individually some had also worked with the others we invited to join, so there were always personal recommendations and shared experiences.

- It took transparency and honesty. The relationships we have built over those years are strong. We have disagreed (a fair amount) on the way, but we have always shared – and even strengthened through our interaction – a commitment to move from fossil carbon feedstocks to a sustainable chemistry based industry.

- It required shared commitment, an understanding of how the different organisations fitted into what will be a wholly new supply chain, and tireless advocacy both within our own organisations – and to anyone who will listen outside them!

- It needed the patience of a saint!

Written by David Bott, Director of Innovation at SCI and originally published on Linkedin

BY DAVID BOTT

A collaboration of 15 organisations is part way through an Innovate UK funded project to turn the carbon dioxide in flue gases into non-ionic surfactants for cleaning products. Many have asked: why we are doing it? how did we build the team? and how things are going? This is the first part of that story.

No one really thinks about the role of chemistry in society. Although everything around us is chemistry – life itself, the natural world, and the material world we have created to add to the natural world – we mostly talk about “chemicals” in a derogatory way. Does society understand how much it relies on carbon-based chemicals? Does chemistry need a PR agency?

Why we need carbon

It is difficult to say exactly when the “synthetic” world started, but the huge expansion came with the use of fractions of the oil and gas we were extracting from the ground as a fuel as material feedstocks about 120 years ago. The petrochemicals supply chain now accounts for about 2.6 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent a year (about 5.7% of the carbon extracted) and is growing at about 8% a year – therefore roughly doubling every 10 years. And the products at the end of the many supply chains that start with these fossil feedstocks range from things we cannot do without (such as disinfectants, soaps, textiles for clothes and so on) to things we “like” to have but would probably fight to keep (such as cosmetics and flying)!

The focus is often on single-use plastic packaging, which makes up about 30% of that 2.6 billion tonnes. But there are many other products that depend on the same source – products for use in the home (carpets, upholstery, paint and adhesives) at about 16%, textiles (mostly for clothes) at about 15%, pharmaceuticals, agrochemicals and fertilisers at about 11%, cleaning products and cosmetics at about 10%, the interiors of cars and their tyres at about 7% and the use in electrical and electronic products (both insulation and cases) at about 4%. Such is society’s use of these products, that we cannot simply stop using them, or make them from something other than carbon. We will need a source of carbon at the same scale.

At this point in the narrative, it is worth pointing out that although many uses of fossil carbon as a fuel can be replaced by alternative technologies, aviation fuel is different. Although there are prototype electric planes for short haul flights, and visions of hydrogen powered planes at some point, the options for long haul air travel look distinctly limited – with really only Sustainable Aviation Fuel as a runner. The aviation industry would need about 1.3 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent a year to keep going at their current rate, so about half that needed to supply our material needs. It faces the same challenge as the carbon based materials – if they do not use fossil carbon, where would it come from?

Where we can get carbon from

The source that gets talked about a lot is “biomass”. At the global level, it is estimated that about 100 million tonnes of biomass is produced each year, roughly half on the land and half in the sea. This equates to roughly 200 million tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent. Most reviews discount the marine biomass as difficult to harvest and then calculate that of the land based only about 8 million tonnes (so, 16 million of carbon dioxide equivalent) a year can be harvested “sustainably”.

Another factor often quoted is the logistical cost of harvesting, since for some crops the energy required to harvest compromises the efficiency of the process. The factor that doesn’t get talked about much is the difference between the biological building blocks and the petrochemical ones we are used to – which would require us to build a different set of supply chains and result in products with different properties.

The second source is the materials made of fossil carbon we have already extracted. There are various estimates of how much plastic is in landfills, but the average seems to be about 5 billion tonnes of plastic – about 15 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent. This would need to be chemically recycled back to feedstocks equivalent to those that underpin the current supply chains.

The third source is the carbon dioxide we have been “storing” in the atmosphere. Since the start of the industrial revolution when our emission of carbon dioxide started in earnest, we have emitted close to 2.2 trillion tonnes of carbon dioxide – half of which is in the atmosphere and the rest has partitioned into the oceans. The problem is that it is very dilute, so you would have to capture a lot of “air” to get meaningful amounts of carbon dioxide – but people are trying!

However, since we are still burning a lot of fossil fuels (and biomass) at the moment, we have flues and chimneys where the carbon dioxide concentration is many times higher. Why not start there and increase the process efficiency with experience?

However, there is a challenge with using carbon dioxide as a source for carbon-based materials. Carbon dioxide is where carbon tends to end up in an oxygen-rich environment – particularly where there is light. It is basically at the bottom of a thermodynamic well and it needs a lot of energy – and green hydrogen – to get it back to those feedstocks we need to go on making things that we want in a way that keep the cost down.

What next?

So, we have a very large problem, some options – each of which has advantages and “issues”, and it will take a long time to change our supply chains, so we need to act fairly quickly before our filling the atmosphere with carbon dioxide does irreparable damage to our environment. We need a plan…

Written by David Bott, Director of Innovation at SCI and originally published on Linkedin

Accelerating the transition to a sustainable global energy system

Welcome to the first in this series from the SCI Energy Group – we’ll be blogging regularly on topics of broad interest across the energy spectrum.

Andy Walker, Chair of the SCI Energy Group.

I’m Andy Walker, and I have the privilege of chairing the Energy Group, which comprises members drawn from industry, research institutes, universities, energy policy bodies, R&D organisations and scientific publishers. We meet regularly to discuss and organise events around the changing energy landscape, exploring challenges and opportunities associated with the clean energy transition.

We inform and influence climate change dialogue and policy in the UK and further afield, by taking a fact-based approach to the challenges and potential solutions, with the ultimate aim of making the global energy system sustainable. We do this by bringing together experts, influencers and other interested parties from across the technology, social science and policy landscape within industry, academia and government. In this way, the SCI Energy Group offers thought leadership, insight and debate around the clean energy transition.

Recently, the Energy Group Committee visited Imperial College London and were given a fascinating tour of the carbon capture and storage pilot plant, which Committee member Alex Bowles had very kindly organised. This was a really interesting visit, hosted by Dr Colin Hale and several enthusiastic and knowledgeable chemical engineering students, focused on the critical role that the capture and long-term storage (and utilisation) of CO2 will play within the clean energy transition. We learned that carbon capture utilisation and storage (CCUS) can play four critical roles in the transition to net zero:

- Tackling emissions from existing energy assets, for example by retrofitting existing fossil fuel-based power and industrial plants, by capturing the CO2 emissions emitted during these processes.

- As a solution for sectors where emissions are hard to abate, such as the in-process emissions during cement manufacture (one of the largest industrial sources of CO2 today).

- As a platform for clean hydrogen production – almost all of the 90 million tonnes of hydrogen generated today is via methane steam reforming, which emits around 10 tonnes of CO2 for every tonne of hydrogen produced.

- Removing CO2 from the atmosphere to balance emissions that cannot be directly abated or avoided (so-called direct air capture, DAC).

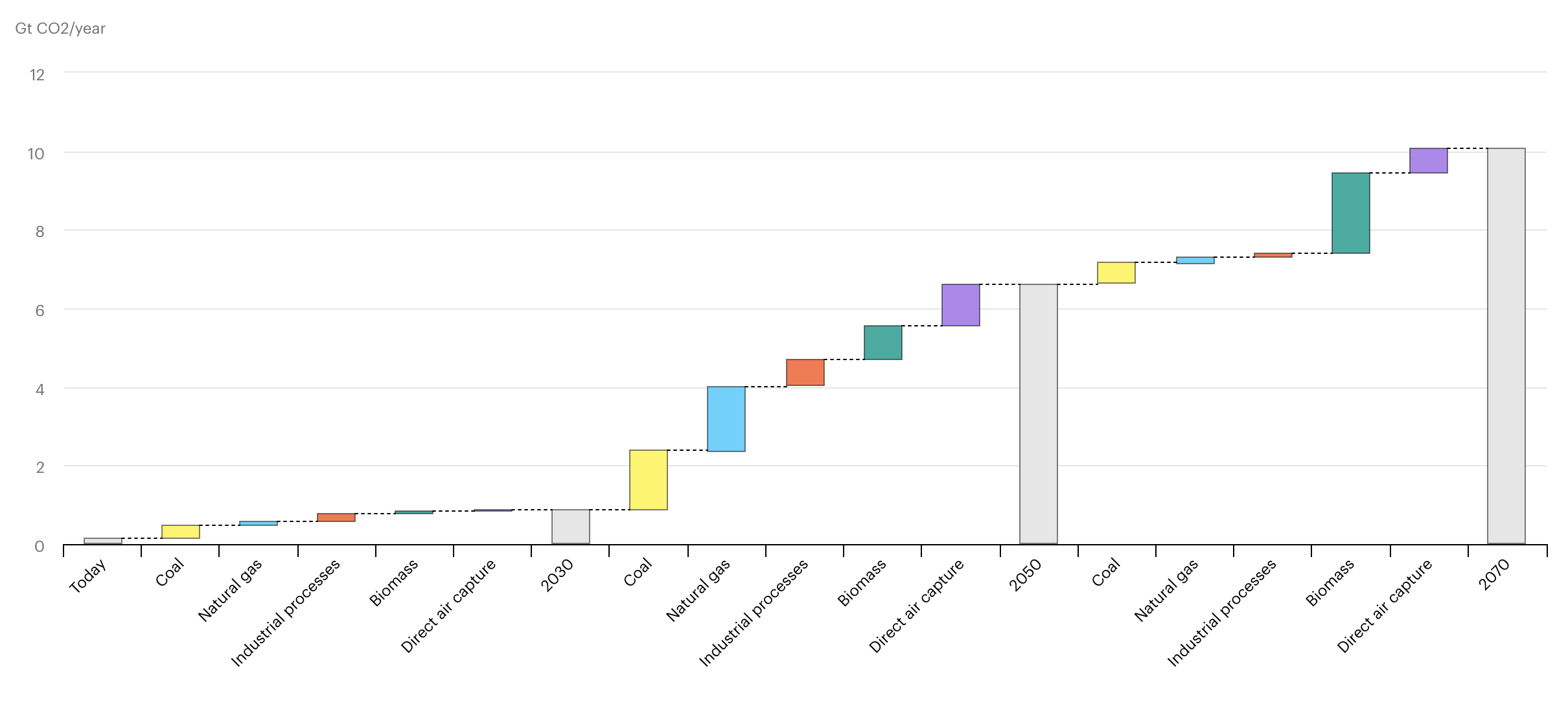

The International Energy Agency (IEA) estimates that the amount of CO2 captured and stored annually in their Sustainable Development Scenario rises to around 9.5 Gt per year by 2070, with another 0.9 Gt CO2 captured and used to make, for example, fuels and chemicals. (Note that a Gigatonne (Gt) is one billion metric tonnes).

IEA, Growth in world CO2 capture by source and period in the Sustainable Development Scenario, 2020-2070, IEA, Paris. Licence: CC BY 4.0

The Energy Group plans to visit several other sites of interest in the coming months, including Drax and the Energy Innovation Centre in Birmingham, so look out for updates from these future visits.

Our next blog will relate to a recent workshop on Energy Storage, which we organised with strong support from Innovate UK/Knowledge Transfer Network. We brought in representatives from industry, academia, government and the finance sector to discuss this broad topic and to identify the key challenges, as well as outline some key policy questions for the government.

We chose this topic because energy storage is a critical part of the clean energy transition, as the world moves towards an increasing dependency on renewable sources of energy, which are inherently intermittent, yet it doesn’t receive enough attention and support from governments around the world. We’re sure you’ll find the outputs from this workshop very interesting!

Creating a paper pulp bottle that holds different liquids was a challenge that led BASF to join forces with Pulpex. Using sustainable chemistry the partners came up with an award-winning formula.

-

Vikki Callaghan, Packaging Project Manager, BASF plc

-

Tony Heslop, Senior Sustainability Manager, BASF plc

-

Scott Winston, CEO Pulpex Ltd

Could you start by explaining how the collaboration and the idea for the product came about?

Vikki: We had an existing relationship with Diageo. BASF and The Innovation Team at Diageo had worked on other projects addressing packaging needs. When the team had this idea for an innovative packaging solution they came to us. The challenge put to us was ‘Do you have the chemistry that will hold many different liquids in a paper pulp bottle?’ I love a challenge and was excited to get talking.

Scott: Having worked with BASF before, they were our natural choice to explore this conundrum. Diageo had the idea and an early proof-of-concept of a paper bottle, but it wasn’t utilising sustainable chemistry. The intellectual property was in place but the transformation of scientific proof-of-principle to scaled commercialised technology wasn’t something that could be done alone. The partnership with BASF naturally continued into Pulpex as it formed and continued to grow, remarkably, throughout the Covid-19 lockdown. BASF’s corporate purpose to create chemistry for a sustainable future was intrinsically aligned to meet our need to deliver a commercialisable product that could be produced at scale.

Tony: Following that first call in November 2019, we got together a couple of weeks later and enjoyed an intense deep dive workshop. This was going to take some time but if successful we knew this could be an impactful innovation. We set to work!

Testing out their bottle in the lab. Image courtesy of Pulpex Ltd.

What hurdles did you overcome in the development of the material?

Tony: The obvious hurdle was the pandemic. There were two years between our first and second face-to-face meeting. My initial thought was how do you drive an innovation process when you can’t get together. Surely constructive and productive collaboration isn’t possible? In fact, the inability to travel meant that we could talk more frequently despite our different geographical locations. Once we’d set up weekly online meetings, which evolved into smaller specialist break out groups, the process actually had many positives and the relationships, as well as the innovation, flourished.

Vikki: Of course, as with any innovation, we experienced technical challenges, too. There was no overall solution because we were looking at very diverse requirements and specifications. Different brand owners with different liquids meant there were many considerations and customised solutions required.

Sustainable packaging is a growing market with new products being launched. Can you explain where your product fits in and how is it different from similar materials?

Scott: Pulpex recognises the need to balance three critical aspects. Firstly, new packaging must continue to deliver established brand equity and meet consumer expectations on quality; secondly, any new packaging must technically deliver on performance through the supply chain starting with filling infrastructure compatibility and through distribution and critically, at end-of-life the packaging must be recyclable in existing infrastructure from collection to enable circularity, or where it does unfortunately escape to the environment, it must degrade and not leave an unintended legacy.

Vikki: The resulting fibre bottle is lightweight and offers brand owners a sustainable, environmentally-friendly alternative to plastic and glass bottles.

The final product. Image courtesy of Pulpex Ltd.

What are the main markets for the packaging? Are you able to comment on customers already using your product?

Tony: The innovation will be aimed at brand owners who want to have an alternative sustainable type of packaging, a product that is suitable for ‘on the go’ and that is easily recyclable through existing waste streams. The technology will hold a range of liquids from alcohol and detergent to shower gel, ketchup and engine oil.

Scott: Trials of the finished product have already started to take place with the most recent being at a corporate five-a-side football tournament at Wrexham AFC in May, where several hundred bottles were put to the test working with Severn Dee Water. Branded especially for the event and designed as a keepsake, the feedback from the public was resoundingly positive and it was great to see our bottles in action supporting those on the pitch.

What are the next steps for the BASF/Pulpex collaboration?

Scott: Having developed such a sustainable alternative packaging, our continuing sprint is scaling up! The technology has been developed and we are expecting to have bottles on shelves soon.

Vikki: We will have our ongoing quest of looking to hold a vast range of liquids and for different brand owners. We will have customised solutions, in different sizes, different shapes… the innovation and collaboration continues.

BASF and Pulpex won the SCI Innovation Enabled by Partnership Award 2023. Image credit: Andrew Lunn Photography

Links to previously published articles and videos (BASF/Pulpex/SCI)

- BASF May 2023 – SCI Award

- BASF August 2021 – Collaboration with Pulpex

- SCI News May 2023 – SCI Award

- Pulpex May 2023 – SCI Award

- Pulpex video

CCU International will supply its carbon capture and refinement system to Flue2Chem – a project led by SCI and Unilever which aims to convert industrial waste gases to create more sustainable consumer products. We caught up with CCU International CEO, Beena Sharma, to talk about her career path, motivations and challenges.

Tell us about your career path to date

I joined the Oil & Gas industry after university and began my career as a behavioural safety specialist, specifically for the construction phase of oil and gas projects. Soon after I joined the industry, I was assigned to an LNG plant in Nigeria for training and experience and eventually ended up at a gas plant in Norway before I returned to the UK. With both a psychology and training background I found myself working within a health, safety and environmental remit for various industries including healthcare, construction, manufacturing, and even the tobacco industry.

Beena and colleague at a gas plant in Norway, 2004. Image credit: Beena Sharma

What made you want to work in science and the environmental technology sector in particular?

When I moved to Scotland six years ago it gave me the opportunity to explore the ‘E’ in Health, Safety and Environment further, which was an area that I was always interested in but rarely got the attention it deserved in the industries I worked in. I volunteered on a Scottish climate change project, and this led me to think more deeply about the scientific and technological advances that were needed to achieve net zero by 2045 in Scotland. I knew this was a huge challenge with education, and changes in habit alone could not solve it.

I began to research solutions for hard-to-abate industries and areas that were a challenge to decarbonise, and set up my first business focused on a novel approach to insulating legacy buildings. I then worked on setting up a group of companies that included a solar PV installation company as well as a cleantech business that utilised an electrolysis technology to ozonate tap water for disinfection.

I was invited by my now business partner to help launch a biotechnical business that could create a circular food economy, taking food waste and creating microalgae for use in industries such as cosmetics, pharmaceuticals, and animal feed. This business incorporated 4 technologies, one of which was carbon capture. After some discussion with potential investors, it became clear that there was a huge interest and demand for carbon capture solutions. This led the team to decide to spin out CCU International as a separate entity and speed up the commercialisation of the technology which had been in development at the University of Sheffield under the lead of Peter Styring, Professor of Chemical Engineering and Chemistry.

Which aspects of your work motivate you the most?

The aspects of what I do that motivates me the most is the educational role that I play as the CEO of the business. I am regularly invited to speak on panels, podcasts, webinars and at conferences to share my knowledge with an industry that is transitioning and eager to learn, grow and incorporate new ways of thinking and doing things. It is extremely rewarding to see that people have come away from listening to me with a new perspective and being inspired to go away, take that learning, incorporate it in their ways of working and become innovators themselves.

According to the UN, carbon capture will be a key technology in achieving net zero. It is extremely rewarding to know that the CCU International technology will be a major contributor to this goal and that we can enable decarbonisation with the technology usage across multiple industries, both large and small, which otherwise would not have been possible.

What have been the biggest challenges for you as an entrepreneur?

As an entrepreneur my biggest challenge has been establishing myself in an industry and environment that is not well represented by women, and in particular women of colour. Often, it comes as a surprise to many that I would be heading up such a business and unfortunately many biases still exist within all genders and backgrounds. It makes it that extra bit harder and there can be a requirement to prove oneself as credible through knowledge or capability before the respect is given.

Image credit: Beena Sharma

The other big challenge has been around the education we provide for all our stakeholders. Innovation is not always welcome, especially in an industry or area where it may seem innovation is not needed. As the saying goes, ‘if it’s not broke, don’t fix it’, so stakeholders tend not to realise there is a problem until we educate them on the solution! And not many can accept there may be a better way of doing things than what they themselves have been doing for years!

What would be your top piece of advice for anyone thinking of starting up their own SME?

Starting up in business is a step that many think about doing but very few actually do. Most would be led to believe that you would need to work for months, maybe years on market research, business planning, strategy etc. before starting a business. My one piece of advice would be to start. Most of what you learn will come from doing. It is essential for entrepreneurs to fail, make the mistakes and learn what not to do next time so you have a better chance of success going forward. Many successful businesses emerge from failure.

What is it about the Flue2Chem project that is unique, what made you want to get involved, and what is the potential difference this project could make?

The Flue2Chem project is aimed at converting industrial waste gases into sustainable materials for use in consumer products. What is unique about the Flue2Chem project is that organisations that would normally be competitors have come together to find a solution for a problem that affects us all – as people, as businesses and as a planet. It is rare to see such cross-industry collaboration on this level and this allows both cross-learning and inspires others to come together, collaborate and innovate to solve problems that affect us all, much like the Flue2Chem project. It is a privilege to be part of the project by contributing our technology to the capture component.

CCU International, carbon capture technology. Image credit: Beena Sharma

The project will play a key role in supporting the UK’s 2050 net zero ambitions by providing a more sustainable feedstock for products such as household cleaning materials. The project could demonstrate how the UK could cut 15-20 million tonnes of carbon dioxide emission each year. The UK imports large quantities of carbon containing feedstocks that we use in the consumer goods industry. The project will demonstrate how we can secure an alternative domestic source of carbon for these goods and also demonstrate how industry can contribute towards achieving net zero.

Why do you think collaboration of this scale is so important?

Industry coming together to solve climate change issues is essential if we are ever to achieve net zero. Collaboration of this scale sends a strong message and emphasises that change in approach is needed and that innovation is key. This inspires others to do the same. Solutions are needed now and by bringing expertise and experience together we learn and adapt quicker. Solutions are needed now – not in years to come.

The impact this project will have has the potential to be huge, across multiple industries and certainly with how we look at not only capturing carbon emissions but also what we can do with the captured carbon dioxide, promoting a circular carbon economy where in time we learn to value carbon dioxide in a way that has never been done before.

Certainly, for the carbon capture storage community, this project will show that there is a use for captured carbon dioxide other than treating it as a waste and sequestering in underground oil reservoirs. Utilising captured carbon dioxide can create revenue streams for any business or process that emits carbon dioxide.

The collaboration demonstrates the commitment from industries to support decarbonisation, of those industries that are hard to abate whilst at the same time building a new UK value chain.

In ‘The Flowers that Bloom in the Spring’ from The Mikado, Gilbert and Sullivan were interpreting the seasons according to their 19th Century climate – but do these flowers still, indeed, bloom in spring? The Meteorological Office’s traditional definitions of the seasons in the UK are:

- Summer from June to August

- Autumn from September to November

- Winter from December to February

- Spring from March to May

Increasingly, climate change is blurring these distinctions, and gardeners are seeing autumn stretching well towards January. Winters in maritime Great Britain are now most severe in February and March, and summer extends into September. The effects of prolonged warm autumns include accelerated growth emergence and flowering of plants which have been thought of as the harbingers of spring.

Phenological studies in the late 20th and early 21st Centuries established that the then-termed ‘early-spring flowering plants’ had accelerated blossoming by as much as four weeks. Now, in the second decade of the 21st Century, it seems this is an underestimate.

Pictured above: Iris unguicularis (styllosa); the Algerian iris

Iris unguicularis (styllosa), the Algerian iris, is renowned as an early flower of spring. It now comes into bloom in late November and very early December, making it an autumn and winter flowering plant. It originates from Algeria, Greece, Turkey, Western Syria, and Tunisia and requires freely draining, light soils with minimal nutrient value. Planted in a south facing border, Iris unguicularis is an undemanding and very colourful addition to the garden. Many early-flowering plants have highly coloured flowers which attract the widest spectrum of insect pollinators.

Pictured above: Cyclamen hederifolium

Similarly, Cyclamen hederifolium (hera meaning “ivy”, folium meaning “leaf”), now flowers vigorously from mid-December, providing colour in the garden in those darkest days prior to the winter solstice. It originates from woodland, shrubland, and rocky areas in the Mediterranean region from southern France to western Turkey and on Mediterranean islands. Once the corms are established it naturalises freely, spreading by self-seeding from explosive seed capsules which cast progeny widely in borders of light, sandy nutrient-free soil.

Pictured above: alyssum (A. saxatile)

The common rockery plant alyssum (A. saxatile), is a perennial herbaceous plant, which rapidly colonises borders and will spread down onto walls providing colour from early January. It is one of the ornamental members of the cabbage family (Brassicaceae) with bright cruciform flowers.

Each of these plants is responding to climatic warming, indicating the loss of traditional seasonality. This impairs relationships between flowering plants and animal pollinators that have carefully evolved for mutual benefit over millennia. The full consequences of these losses will be apparent in years and decades to come.

Professor Geoff Dixon is author of Garden practices and their science, published by Routledge 2019.

What effect do vaping and air pollution have on your heart, and how could a light-powered pacemaker improve cardiovascular health?

It seems that every day, scientists are learning more about the factors affecting cardiovascular health and are coming up with novel ways to keep our hearts ticking for longer. Here are three interesting recent developments.

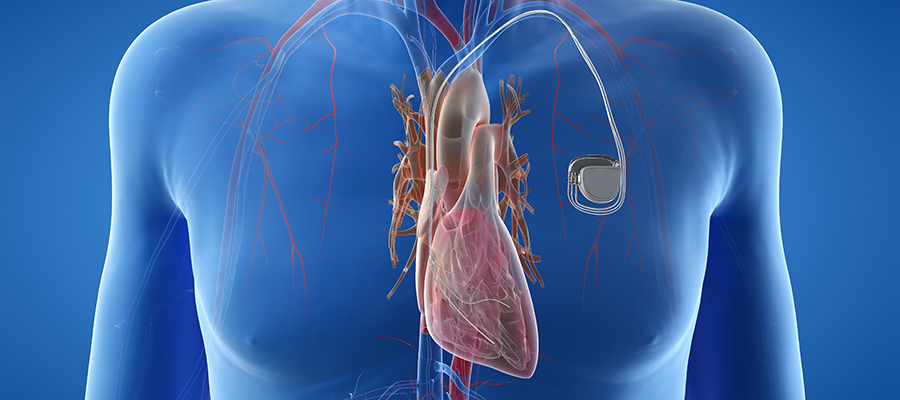

A less painful pacemaker

One of the problems with existing pacemakers is that they are implanted into the heart with one or two points of connection (using screws or hooks). According to University of Arizona researchers, when these devices detect a dangerous irregularity they send an electrical shock through the whole heart to regulate its beat.

These researchers believe their battery-free, light-powered pacemaker could improve the quality of life of heart disease patients through the increased precision of their device.

The way existing pacemakers work can be quite painful for heart disease patients.

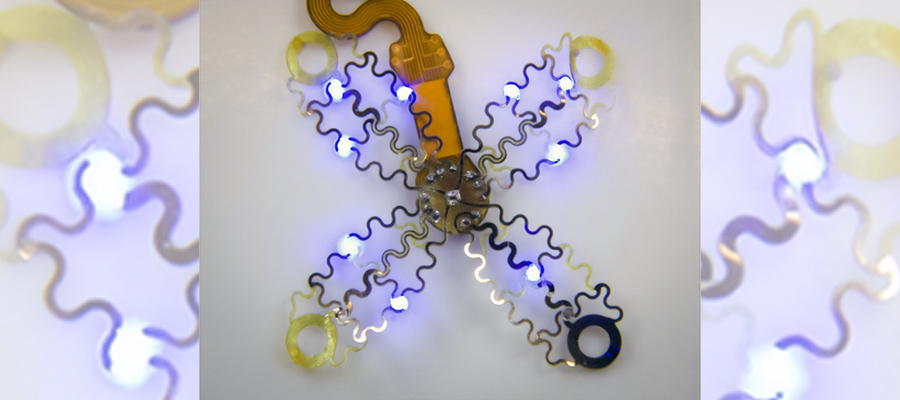

Their pacemaker comprises a petal-like structure made from a thin flexible film (that contains light sources) and a recording electrode. Like the petals of a flower closing up at night, this mesh pacemaker envelops the heart to provide many points of contact.

The device also uses optogenetics – a biological technique to control the activity of cells using light. The researchers say this helps to control the heart far more precisely and bypass pain receptors.

‘Right now, we have to shock the whole heart to do this, [but] these new devices can do much more precise targeting, making defibrillation both more effective and less painful,’ said Igor Efimov, professor of biomedical engineering and medicine at Northwestern University.

‘Current pacemakers record basically a simple threshold, and they will tell you,’ added Philipp Gutruf, lead researcher and biomedical engineering assistant professor. ‘This is going into arrhythmia, now shock, but this device has a computer on board where you can input different algorithms that allow you to pace in a more sophisticated way.’

Another potential benefit is that the light-powered device could negate the need for battery replacement, which is done every five to seven years. That use of light to affect the heart rather than electrical signals could also mean less interference with the device’s recording capabilities and a more complete picture of cardiac episodes.

The device uses light and a technique called optogenetics, which modifies cells that are sensitive to light, then uses light to affect the behavior of those cells. Image by Philipp Gutruff.

>> See how Bright SCIdea winner Cardiatec uses AI to improve heart disease treatment.

The danger of vaping?

We don’t know a lot about the long-term effects of vaping because people simply haven’t been doing it long enough, but a recent study from the University of Wisconsin (UW) suggests that it could be bad for the heart.

Researchers selected a group of people who had used nicotine delivery devices for 4.1 years on average, those who smoked cigarettes for 23 years on average, and non-smokers and compared how their hearts behaved after smoking (the first two groups) and after exercise.

The researchers noticed differences minutes after the first two groups smoked or vaped. ‘Immediately after vaping or smoking, there were worrisome changes in blood pressure, heart rate, heart rate variability and blood vessel tone (constriction),’ said lead study author Matthew Tattersall, an assistant professor of medicine at the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health.

The lack of long-term data means we still don’t know the effect of vaping.

Those who vaped also performed worse on the four exercise parameters compared to those who hadn’t used nicotine. Perhaps the most startling finding was the post-exercise response of those who had vaped for just four years compared to those who had smoked tobacco for 23 years.

‘The exercise performance of those who vaped was not significantly different from people who used combustible cigarettes, even though they had vaped for fewer years than the people who smoked and were much younger,’ said Christina Hughey, fellow in cardiovascular medicine at UW Health, the integrated health systems of the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

The influence of lead and air pollution

We know that smoking and passive-smoking are bad for our hearts, but some overlook the effect of other environmental toxins, especially those common to specific geographical regions.

A collaborative study including US and UK researchers has found a divergence in the types of environmental contaminants that contribute to cardiovascular ailments in both countries, aside from the prevalent smoking-related heart disease.

Hopefully, the growth in electric vehicle use will reduce air pollution

The study found that lead-related poisoning is more common in the US, whereas air pollution has a more damaging effect in the UK due mainly to increased population density. The researchers found that 6.5% of cardiovascular deaths were associated with exposure to particulate matter over the past 30 years compared to 5% in the US.

The one plus is that research has found that there has been a steady decline in cardiovascular deaths stemming from lead, smoking, secondhand smoke and air pollution over the past 30 years. Nevertheless, it will be of little comfort to those walking in the trail of exhaust fumes in cities.

‘More research on how environmental risk factors impact our daily lives is needed to help policymakers, public health experts, and communities see the big picture,’ said lead author Anoop Titus, a third-year internal medicine resident at St. Vincent Hospital in Worcester, Massachusetts.